It’s Time for Change

By Lee Spiller

Director, CCHR Texas

Published by CCHR International

The Mental Health Industry Watchdog

June 29, 2016

According to a recent press release from the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP), Texas continues to rank as one of the worst states in the drugging of vulnerable seniors with antipsychotic drugs, in spite of several significant attempts at reform.

Data from the federal Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) shows that about 1 in 5, or 19,000 each month, in Texas nursing homes were inappropriately being given antipsychotic drugs.[1] Antipsychotics, originally intended for persons in psychotic states, have been increasingly used in vulnerable populations such as the elderly in nursing homes.

Unfortunately, the use of powerful psychotropic drugs on seniors has been a continuing problem in Texas. In 2001, several groups including Texas Watch, the Citizens Commission on Human Rights-Texas, AARP, National Association of Social Workers, Texas Advocates for Nursing Home Residents, and others formed a coalition to address many concerns surrounding care in nursing homes, including the use of powerful psychotropic drugs. At that time, Texas passed a law ensuring that nursing home residents, like populations in other settings such as psychiatric hospitals, had a right to be warned about the risks and benefits of psychotropic drugs, and that the process be reduced to writing and signed by the patient or the patient’s legally authorized representative.[2]

It is unconscionable that some of Texas’s most vulnerable citizens continue to be subjected to powerful and dangerous drugs. While the informed consent law does a wonderful job for those who have significant family involvement or frequent contact with friends who are interested in their welfare, it is obvious that many seniors are still falling prey to questionable or potentially fraudulent drugging.

In 1997, a representative of the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) testified before a U.S. House subcommittee that “For the opportunistic provider, a nursing home represents a vulnerable elderly population in a single location and the opportunity for multiple billings.”[3]

Also in 1997, CCHR and Texas’s hospital regulators became aware of allegations that nursing home residents, some of whom were incapable of consenting, were allowed to sign themselves into a psychiatric hospital, with some even “consenting” to electroconvulsive therapy (ECT).[4]

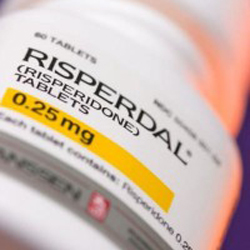

In a proposed $2.2 billion federal settlement from 2013 resolving various allegations including off-label marketing, the maker of the antipsychotic drug Risperdal admitted that it promoted the drug to health care providers for treatment of psychotic symptoms and associated behavioral disturbances exhibited by elderly, non-schizophrenic dementia patients.[5] This was not the only drug company that settled such allegations. With between 22-86% of antipsychotic prescriptions to the elderly being for off-label uses, it begs the question: Did we accept a cash transfusion but fail to stop the bleeding?[6]

In a proposed $2.2 billion federal settlement from 2013 resolving various allegations including off-label marketing, the maker of the antipsychotic drug Risperdal admitted that it promoted the drug to health care providers for treatment of psychotic symptoms and associated behavioral disturbances exhibited by elderly, non-schizophrenic dementia patients.[5] This was not the only drug company that settled such allegations. With between 22-86% of antipsychotic prescriptions to the elderly being for off-label uses, it begs the question: Did we accept a cash transfusion but fail to stop the bleeding?[6]

Antipsychotic drugs are associated with weight gain, diabetes, high cholesterol, heart disease, and of great concern for the elderly: increased fall risk.[7] Unfortunately, these are not the only risks for the elderly.

In 2005, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) required a black box warning—the FDA’s most stringent warning—on the use of atypical (newer) antipsychotic drugs on elderly dementia patients citing an increased risk of death. In 2008, they extended the black box warning to all antipsychotics.[8]

AARP Texas Director, Bob Jackson told reporters that when the Texas legislature meets in 2017, his organization will be urging lawmakers to prioritize and pass legislation improving nursing home quality. CCHR strongly supports this stance.

The Texas legislature took several steps in 2015 to try to improve nursing home quality. It’s rather obvious that more needs to be done. Given that use of antipsychotic drugs continues to be a problem across age groups from foster care children to elderly nursing home residents, we would support an entire restraint reduction initiative, including curbing the inappropriate use of antipsychotic drugs. The Citizens Commission on Human Rights stands ready to work with anyone who has the political will to say enough is enough.

And certainly the vulnerable populations of Texas deserve better.

References:

[1] Zoey Hanrahan, “Texas Ranks Among Worst Offenders in Prescribing Antipsychotic Medications,” San Angelo Live, June 22, 2016, http://sanangelolive.com/news/health/2016-06-22/texas-ranks-among-nations-worst-offenders-prescribing-antipsychotic.

[2] Senate Bill 355, enrolled version, 2001: http://www.legis.state.tx.us/tlodocs/77R/billtext/html/SB00355F.htm.

[3] GAO Testimony, “Nursing Homes: Too Early to Assess New Efforts to Control Fraud and Abuse,” April 16, 1997, http://www.gao.gov/assets/110/106845.pdf.

[4] Scott Parks, “Shock treatment scrutinized in the wake of woman’s death: Lawmakers want to halt unnecessary treatments,” Dallas Morning News, May 24, 1997, http://www.ect.org/news/death.html.

[5] “Johnson & Johnson to Pay More Than $2.2 Billion to Resolve Criminal and Civil Allegations,” US Department of Justice, Press Release, November 4, 2013, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/johnson-johnson-pay-more-22-billion-resolve-criminal-and-civil-investigations.

[6] Carton et al., “Off-label Prescribing of Antipsychotics in Children, Adults, and the Elderly: A Systematic Review of Recent Prescription Trends,” Curr Pharm Des., 2015;21(23):3280-97, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26088115.

[7] Op Cit., Zoey Hanrahan.

[8] “Information for Health Professionals: Conventional Antipsychotics,” US F.D.A., June 2008, http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformation

forPatientsandProviders/ucm124830.htm.