The Dallas Morning News

By Jessica Huesman

July 24, 2015

Federal regulators are taking the rare step of kicking one of North Texas’ largest psychiatric hospitals out of the Medicare and Medicaid programs for leaving patients in “immediate jeopardy” of injury or death.

State officials, meanwhile, said Friday that they may revoke Timberlawn Mental Health System’s license, forcing it to shut down and leaving the region scrambling for enough beds for mentally ill patients.

Timberlawn flunked a make-or-break inspection, a final chance to prove it could fix an array of problems after promising improvements for months.

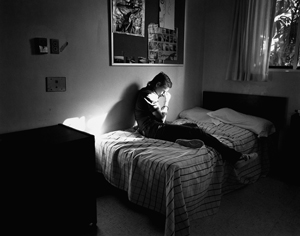

The U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services found that unlicensed personnel were monitoring patients and some patients were going more than 12 hours without seeing a nurse. Electrical cords and other unsafe objects remained in rooms within reach of suicidal patients.

“These practices posed an immediate jeopardy to the health and safety of patients,” inspectors said in a report.

The state said it is moving quickly to evaluate its enforcement options.

“The issues have been egregious and incredibly disheartening. We are absolutely looking at the full range of penalties, including license revocation,” said Carrie Williams, a spokeswoman for the Texas Department of State Health Services. “Our inspectors have been in and out of the facility since February, citing issues and not seeing progress. It’s turned into a critical situation.”

State officials also are determining whether any referrals need to be made to law enforcement or licensing boards, Williams said.

Timberlawn CEO Shelah Adams said the hospital is still operating “with no disruption of services” but offered no information on how it would handle the loss of funding. She said Timberlawn is “hopeful” improvements to the facility might lead to an “abatement” of the funding cut.

But David Wright, acting regional director for the CMS, as the federal agency is known, said it would not consider such a move under any circumstances. “There are no additional opportunities for compliance,” he said.

The stakes are high at Timberlawn, part of the Pennsylvania-based Universal Health Systems [Services] hospital chain. Roughly a third of its $65 million in total patient revenue came from Medicare and Medicaid in 2013, according to figures from the American Hospital Directory.

Patient’s hanging

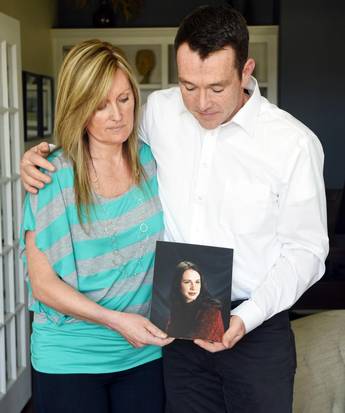

Collette Riel and Brett Bennetts fault Timberlawn in Dallas for the death of their sister, Brittney Bennetts, who committed suicide while at Timberlawn. “This is just negligence,” Riel says.

With 144 beds, Timberlawn has served the community for more than a century. It came under scrutiny after a patient committed suicide in December by hanging herself from a kind of doorknob that the hospital itself had previously identified as a suicide risk but failed to replace.

Since then, state and federal regulators have consistently found accessible items that could be used for patient self-harm, instances of improper care for suicidal patients, and inadequate training and staffing of nurses in the facility. They’ve also found that staff at Timberlawn falsified patient records to avoid scrutiny.

Timberlawn will stop receiving Medicare and Medicaid payments on Aug. 7. It can continue to accept patients through private funds. But if it loses its license and can’t treat patients, they’ll have to go to other facilities, such as Green Oaks Hospital and Dallas County’s Parkland Memorial Hospital. All three facilities receive patients who have been apprehended by police.

CMS said about 240 beds exist at other hospitals for psychiatric patients, enough to handle Timberlawn’s Medicare and Medicaid patient population. Timberlawn now has about 70 psychiatric patients who rely on government funding. But if the hospital shuts down altogether, it could create at least a temporary shortage around the region.

“Something like this creates a shock to the entire behavioral health system here in North Texas,” said Parkland spokesman Mike Malaise. “The bottom line is North Texas has a shortage of behavioral health beds available to the patients Parkland serves.”

Even if other facilities can absorb the patients, area health officials say, Timberlawn’s specialty in handling children’s cases would be difficult to immediately replace.

“Timberlawn has been what we call the front door for children and adolescents,” said Sherry Cusumano, executive director of community education and clinical development at Green Oaks, which occasionally stops taking patients because it reaches capacity. “I would imagine there will be a tremendous need there if they are no longer going to handle that volume.”

Cusumano said she’s worked in health care since 1977 and has “never seen anything like this happen.”

Cutting off Medicare and Medicaid funding from a hospital is “very rare,” said Wright, the CMS official. He said Timberlawn is one of only two Medicare-certified hospitals out of the 531 in the state to have lost funding since 2014.

Wright said Timberlawn can contest the decision in court, but payments would still be stopped while both parties await a hearing.

The facility can also start over, applying anew for Medicaid and Medicare funding. But the hospital would need to fix all identified issues and undergo extensive review that could take many months.

Failed surveys

“These practices posed an immediate jeopardy to the health and safety of patients,” inspectors said of Timberlawn in a report.

The cut comes after several rounds of unannounced surveys conducted by CMS starting in February. All surveys found the hospital was out of compliance. Surveys between June 29 and July 1 were its final chance to remain in the program.

The final survey shows that, on at least one occasion, staff at Timberlawn falsified records. After a patient swallowed a metal object while at Timberlawn, a supervisor asked a nurse to change her notes and exclude relevant medical information.

When CMS surveyors asked why, the supervisor said it was “because of the recent safety issues identified by the state.”

Timberlawn previously also told CMS that all ligature risks had been removed from patient rooms. But the most recent survey found that faucets in the juvenile wing of the facility could be used by patients to hang themselves. All of the patients in the rooms identified to have such faucets were deemed at risk of suicide.

The hospital’s safety specialist also told surveyors she did not think the faucets were an issue, and staff had not been provided any training to identify them as such.

Surveyors also found nurses were frequently unavailable to assist patients in distress and routinely did not check on suicidal patients at their assigned intervals. On one occasion, a nurse did not attend to a patient in detox for an entire night. On another, surveyors found that no nurse had been assigned to the assessment area for patients brought in by the Dallas Police Department, many of whom are at immediate risk of suicide or self-harm.

Management issues also presented a problem. CMS found that “the medical director failed to adequately monitor and evaluate the care provided to patients at the facility” and that patients were frequently given pre-printed care plans rather than plans individually tailored to their needs.