Los Angeles Daily News

November 24, 2014

By Karen de Sá

Olivia Hernandez always trusted the doctors who scribbled out prescription after prescription for the heavy-duty psychiatric drugs that clouded her teenage years in foster care.

Now, she feels “betrayed.”

Three of her former doctors are among a chosen group of California foster care prescribers who received gifts and payments for meals, travel, speaking and industry-sponsored research from the world’s biggest pharmaceutical companies.

An investigation by this news organization has found that drugmakers, anxious to expand the market for some of their most profitable products, spent more than $14 million from 2010 to 2013 to woo the California doctors who treat this captive and fragile audience of patients at taxpayers’ expense.

Drugmakers distribute their cash to all manner of doctors, but the investigation found that they paid the state’s foster care prescribers on average more than double what they gave to the typical California physician.

The connection raises concerns that Hernandez and many other unsuspecting youth have been caught in the middle of a big-money alliance that could be helping to drive the rampant use of psychiatric medications in the state’s foster care system.

Olivia Hernandez, 22, a UCLA student, was prescribed as many as four psychiatric medications at a time as a foster youth in Southern California. (Dai Sugano/Bay Area News Group)

“It sucks that the people marketed it that way, but that’s not that shocking. I’m more mad at the doctors for just going along with it,” said Hernandez, 22, who was prescribed as many as four of the drugs at a time as a foster youth in Southern California.

Overall, drugmakers reported payments to 908 doctors — well over half of those who prescribed psych medications to the state’s foster children, according to this news organization’s analysis of prescribing data and four years of pharmaceutical company payments compiled by the public interest journalism nonprofit ProPublica. And those who prescribed the most typically received the most, the analysis found.

The results provide the most comprehensive look to date at the pharmaceutical industry’s influence on the doctors who treat the 60,000 kids in the country’s largest foster care system — a lucrative target because Medi-Cal pays the bill with little scrutiny.

One Sacramento doctor raked in more than $310,000 in four years to give promotional speeches and an extra $8,500 in meals, records show. Another 224 doctors each got more than $500 in meals, and two of them each received more than $20,000 for travel. The biggest payments went for research, with two Southern California doctors each receiving more than $2 million to conduct drug company-sponsored trials.

Doctors who accept the drug companies’ offerings say they aren’t influenced, and the pharmaceutical industry defends its partnerships as a necessity for developing the lifesaving drugs of tomorrow.

“The kind of medical innovation that we have in this country wouldn’t happen without a robust dialogue between industry and physicians,” said John Murphy, assistant general counsel for the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America.

But critics say the drug companies are disguising investments in the name of science to reward doctors who in turn boost the industry’s bottom line.

“These figures suggest these doctors are not looking out primarily for the kids’ interests,” said UCLA social welfare professor David Cohen, who has studied medication use in the foster care system and drug company influence. “They suggest many doctors are looking out for their financial interests, and we should all be wary.”

The findings are especially disturbing because of the growing evidence that psychiatric drugs are being overprescribed to California’s foster children despite their significant side effects, the subject of this news organization’s yearlong investigation “Drugging Our Kids.” The news organization previously reported that almost 1 in every 4 adolescents in California foster care has been prescribed psychotropic medications, often to manage troublesome behavior rather than treat the severe mental illnesses for which they are approved.

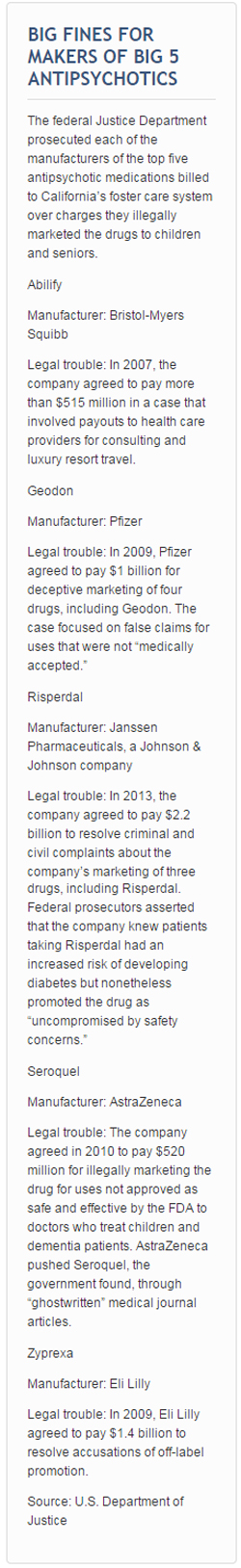

While the federal government has cracked down in recent years on how drug companies market powerful antipsychotic drugs to the elderly and children, the industry’s investment in courting doctors appears to still be paying off: California taxpayers spend more on psychotropic drugs than on any other kind of medication prescribed to foster children, according to a decade of Medi-Cal spending data revealed by this news organization in August.

TARGETING DOCTORS

The 17 drugmakers who reported payments steered more than $11.3 million in research funds to doctors who prescribe psychotropic drugs to the state’s foster kids.

The state’s Department of Health Care Services has provided only limited information to the news organization about the prescribing history of individual doctors who treat foster kids, so it’s difficult to gauge the influence of drug company payments.

But the news organization’s analysis provides a glimpse into how pharmaceutical companies are targeting these doctors. The ones who received the highest payments range from child psychiatrists in rural outposts to top-tier researchers at publicly funded universities, including UCLA and UC San Francisco. The data showed:

Foster care prescribers reap nearly 2½ times more than the typical California doctor: From 2010 to 2013, almost 30 percent of all California doctors — and about 35 percent of foster care prescribers — received at least $100 from drug companies. But while the California doctors in that group received an average of $10,800 apiece over the four-year period, foster care prescribers typically received far more, nearly $25,000 each.

Frequent prescribers are generally rewarded the most: Doctors who wrote more than 75 prescriptions to foster children in a year received more drug company payments than those who wrote fewer. While the margin fluctuated from year to year, on average the higher prescribers in the most recent fiscal year collected almost four times — or about $10,000 more — than the lower prescribers in 2013.

The bulk of the payments fund drug company-sponsored research: The 17 drugmakers who reported payments steered more than $11.3 million in research funds to doctors who prescribe psychotropic drugs to the state’s foster kids, with Eli Lilly — maker of the antipsychotic drug Zyprexa — leading the pack by spending $6 million.

The companies kept some of their big researchers busy in other ways: Six of the doctors who earned among the largest research grants also tallied a cumulative total of almost $400,000 in speaking and consulting fees and another $45,000 in travel and meals.

THE DEBATE OVER SPONSORED RESEARCH

Adriane Fugh-Berman, a pharmacology professor at Georgetown University’s Medical Center in Washington D.C., says doctors are influenced by pharmaceutical companies’ swag, meals and other gifts. (Dai Sugano/Bay Area News Group)

The drug companies’ reports give no specifics on how their research money is spent, but doctors conducting the research say the funds are used on a variety of expenses to run clinical trials of the companies’ drugs. Many doctors say industry-sponsored research is a must with so little federal funding available to advance medicine.

“It’s only fair that pharmaceutical companies fund the research that they’re going to be reaping profits from,” said George Fouras, a San Francisco child psychiatrist and spokesman for the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. “I know that it has to happen this way, but as a consumer of the research I might be somewhat skeptical.”

Numerous studies in recent years confirm that skepticism. For example, a 2007 study in BMJ, formerly known as the British Medical Journal, found “results and conclusions of randomized, controlled trials with financial ties to one drug company are more likely to favor the sponsor’s products.”

“Many people claim that ‘science is science,’ but it’s not that h ard to find what you want with most research studies,” said Jerome Hoffman, a emergency medicine specialist at UCLA and critic of the pharmaceutical industry’s influence. “Even negative studies can often be made to look positive.”

ard to find what you want with most research studies,” said Jerome Hoffman, a emergency medicine specialist at UCLA and critic of the pharmaceutical industry’s influence. “Even negative studies can often be made to look positive.”

Drug companies buy doctors lunch or sponsor speaker dinners to discuss their latest products. Pfizer picked up the tab for more than $105,000 on dining, more than any other company in the news organization’s analysis, which also found that 7 percent of all foster care prescribers took at least $1,000 in meals during the four-year period, compared with 2 percent of all California doctors.

“People are more receptive to messages of any kind when they’re eating,” said Adriane Fugh-Berman, an associate pharmacology professor at Georgetown University’s Medical Center who has published extensively on drug company influence. “Food is the great lubricant.”

In a study of doctors in the nation’s capital, Fugh-Berman and colleagues also found that psychiatrists who accepted Medicaid were top targets of antipsychotic drugmakers and received a disproportionate share of gifts.

Like most states, California has no restrictions to prevent doctors who treat patients on Medi-Cal, the state’s public health system, from accepting payments from drugmakers. Massachusetts’ Physician Gift Ban Law prohibits the industry from treating doctors to trips and other types of entertainment, but it rolled back a provision that outlawed most gifts or meals. The pharmaceutical industry has instituted its own voluntary code with similar restrictions.

But even small gestures such as meals and free samples pay dividends, experts say.

“As doctors, we like to think and will often say that we are not influenced much by marketing,” said Pennsylvania neurologist Richard Paczynski, who has testified against drug companies over the illegal promotion of antipsychotics. “But we shouldn’t be naive and think these drug companies would be spending as much as they do reaching out to us if it wasn’t paying off.”

Read the rest of the article here: