Mercury News – August 25, 2014

Story by Karen de Sá

Photographs and video by Dai Sugano

They are wrenched from abusive homes, uprooted again and again, often with their life’s belongings stuffed into a trash bag.

Abandoned and alone, they are among California’s most powerless children. But instead of providing a stable home and caring family, the state’s foster care system gives them a pill.

With alarming frequency, foster and health care providers are turning to a risky but convenient remedy to control the behavior of thousands of troubled kids: numbing them with psychiatric drugs that are untested on and often not approved for children.

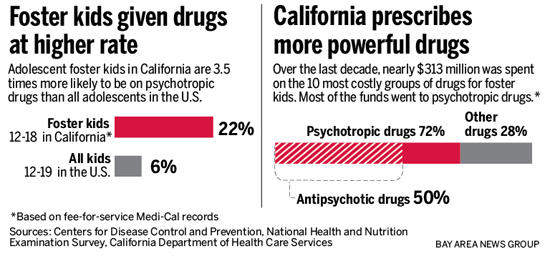

An investigation by this newspaper found that nearly 1 out of every 4 adolescents in California’s foster care system is receiving these drugs — 3 times the rate for all adolescents nationwide. Over the last decade, almost 15 percent of the state’s foster children of all ages were prescribed the medications, known as psychotropics, part of a national treatment trend that is only beginning to receive broad scrutiny.

“We’re experimenting on our children,” said Los Angeles County Judge Michael Nash, who presides over the nation’s largest juvenile court.

A year of interviews with foster youth, caregivers, doctors, researchers and legal advocates uncovered how the largest foster care system in the U.S. has grown dependent on quick-fix, taxpayer-funded, big-profit pharmaceuticals — and how the state has done little to stop it.

“To be prescribing these medications so extensively and so, I think, thoughtlessly, with so little evidence supporting their use, it’s just malpractice,” said George Stewart, a Berkeley child psychiatrist who has treated the neediest foster children in the Bay Area for the past four decades. “It really is drugging them.”

The state official who oversees foster care, Department of Social Services Director Will Lightbourne, concedes drugs are overused, but insists his department is wrapping its arms around the problem: “There’s a lot of work to be done here to make sure we do things right.”

…

But there is substantial evidence of many of the drugs’ dramatic side effects: rapid-onset obesity, diabetes and a lethargy so profound that foster kids describe dozing through school and much of their young lives. Long-term effects, particularly on children, have received little study, but for some psychotropics there is evidence of persistent tics, increased risk of suicide, even brain shrinkage.

Sade Daniels, of Hayward, became so overweight in her teens, that at age 26 her bathroom mirror still taunts and embarrasses her. Mark Estrada, a 21-year-old from Anaheim, said he felt too “zoned out” to focus on high school and so groggy he was cut from his varsity basketball team.

And Rochelle Trochtenberg, now 31 and living in Eureka, still struggles to bring a glass to her lips because her hands are so shaky from the years she spent on a shifting mix of lithium, Depakote, Zyprexa, Haldol and Prozac, among others. When people ask, she tries to cover it up with remarks about a possible hereditary condition.

The truth is too painful to explain, she said. “I don’t want to tell people I have a tremor because I was drugged for my whole adolescence.”

Questionable prescribing revealed

Despite the concerns, state officials have been slow to even reveal foster care prescribing patterns in California. This newspaper and its lawyers spent nine months negotiating with the Department of Health Care Services for data that is public under state and federal law, as long as individuals cannot be identified.

The 10 years of data begins in 2004 and — even though the state continues to resist many of this newspaper’s requests — provides the most comprehensive look yet at psychotropic medication use on California’s foster kids. The newspaper also interviewed more than 175 people, including more than 30 current and former foster youth throughout the state.

The findings, which will be examined here and in future stories, include:

Growing use of antipsychotics to treat bad behavior: Of the tens of thousands of foster children placed on psychotropic drugs over the past 10 years, nearly 60 percent were prescribed an antipsychotic, the class of psychotropic medications with the highest risks. That figure stunned experts in the field and alarmed officials who oversee the state’s foster care system. The Food and Drug Administration authorizes antipsychotics for children only in cases of severe mental illness, but evidence suggests doctors often prescribe them to California foster children for behavior problems — a legal but controversial practice that critics say should be limited.

Growing use of antipsychotics to treat bad behavior: Of the tens of thousands of foster children placed on psychotropic drugs over the past 10 years, nearly 60 percent were prescribed an antipsychotic, the class of psychotropic medications with the highest risks. That figure stunned experts in the field and alarmed officials who oversee the state’s foster care system. The Food and Drug Administration authorizes antipsychotics for children only in cases of severe mental illness, but evidence suggests doctors often prescribe them to California foster children for behavior problems — a legal but controversial practice that critics say should be limited.

Multiple psych meds common but dangerous: In many cases, doctors piled on prescriptions: 12.2 percent of California foster children who received a psych drug in 2013 were prescribed two, three, four or more psychotropic medications at a time — up from 10.1 percent in 2004. These drug combinations often fall in uncharted medical territory, with no scientific evidence that young brains aren’t being harmed.

Read the rest of the article here: http://webspecial.mercurynews.com/druggedkids/