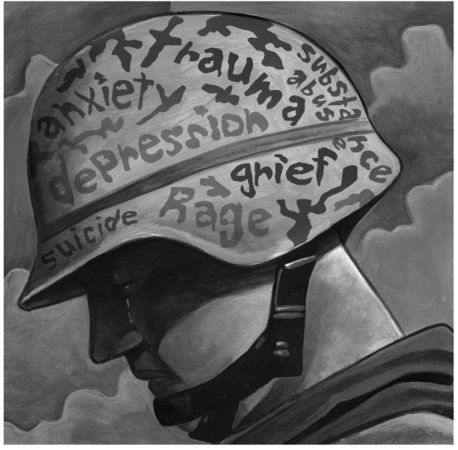

Leaving the war is half the battle. Leaving the war behind is the other. How everyday efforts can help veterans be civilians again.

Philly.com

By David Sutherland & Paula Caplan

February 10, 2013

There’s no mystery, but people talk as though there is. Some leaders in the Department of Veterans Affairs, as well as some psychotherapists and other citizens, express puzzlement about why, in the last 11 years, the rates of suicides, family breakdown, substance abuse, and homelessness among war veterans have steadily risen.VA Secretary Eric K. Shinseki spoke recently about suicide without offering explanations beyond “some increased level of stress,” scant improvement over a Defense Department press release titled “Uncertainty About Military Suicides Frustrates Services.”

There’s no mystery, but people talk as though there is. Some leaders in the Department of Veterans Affairs, as well as some psychotherapists and other citizens, express puzzlement about why, in the last 11 years, the rates of suicides, family breakdown, substance abuse, and homelessness among war veterans have steadily risen.VA Secretary Eric K. Shinseki spoke recently about suicide without offering explanations beyond “some increased level of stress,” scant improvement over a Defense Department press release titled “Uncertainty About Military Suicides Frustrates Services.”

Is there really a mystery? Do we really not know why 22 veterans take their own lives every day – 70 percent among vets over age 50? Or why veterans are 50 percent more likely to end up without a home than other Americans? Why the divorce rate among military couples has increased 42 percent during the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq? How it is that nearly two million veterans from all wars are substance abusers?

Based on our years of on-the-ground and clinical experiences, respectively, working with veterans, we believe there is no mystery. Four primary factors cause the emotional devastation and moral anguish that plague so many who have been to war.

First, war is vile. Imagine holding in your arms a 5-year-old girl shot in the face by an insurgent because her father served in the Iraqi police force. Or driving in a convoy, with children running playfully beside you, when a terrorist drives his pickup into the children, killing them all. The horror and barbarism are chilling: comrades die, innocents are maimed, local “friendly” forces betray you.

Contributing to veterans’ suffering is the soul-crushing isolation most experience when they return home. Friends and family rarely know what these men and women have experienced, and many veterans hesitate to talk openly for fear of upsetting loved ones, facing harsh judgment, or simply not being understood. For many, the silence and isolation continue for decades.

Increasing the isolation is the fact that people traumatized by war are often mislabeled as mentally ill. The “disorder” labels most often used – post-traumatic stress, major depressive, generalized anxiety, bipolar – further distance veterans from their communities. Civilians assume that they are unqualified to help, believing that only therapists have the needed tools. Nothing we propose precludes veterans from seeking help from a therapist. Anyone who is suffering deserves attention and care, and for some, that might include traditional approaches used by therapists. However, not all suffering constitutes a mental disorder, and our nation’s knee-jerk reaction to call all war trauma “mental illness” ends up hurting veterans.

Finally, psychotropic drugs often intensify the veterans’ suffering and isolation. Once labeled with a mental illness, veterans are routinely prescribed cocktails of psychiatric drugs that alter in troubling ways their emotions and cognition. Tragically, the kinds of harm the drugs can cause include precisely those that are increasing among service members and veterans: suicide, family breakdown, substance abuse, and homelessness. Many senior Defense officials have voiced their concern about the dangerous effects of these drugs.

There are many effective and nonpathologizing solutions to the epidemic problems destroying our war veterans. All of us – including the military, the VA, and mental-health professionals – must stop automatically labeling war veterans “mentally ill.” Being shaken to the core by war is a deeply human reaction. Calling it mental disorder alienates veterans from themselves and their communities and causes moral anguish. It blinds civilians to veterans’ pain and cuts civilians off from their common humanity with those who have gone to war.

There are low-risk ways that community leaders or any citizen can help veterans heal, primarily helping them create or connect, which in turn will help their communities. Unlike drugs, these do not have dangerous side effects, and they could not differ more from the isolation intensified by labeling and drugging. These options include involving veterans in mentoring, volunteering, meditation, promoting the arts, sports and recreation, nonprofit leadership, and political action, and providing them service animals for connection and comfort. The recent “A Better Welcome Home” conference at Harvard Kennedy School’s Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation featured several examples. (Visit http://bit.ly/OToAwc for more information.)

Even something as simple as listening can make a difference. Veterans taking part in the Welcome Johnny and Jane Home project reported that having the chance to tell their stories was helpful and healing, according to a study conducted at the Harvard Kennedy School.

And citizens can speak up. Our military and political leadership need to hear that Americans care about our veterans and are willing to do their part to help. As our military men and women continue to return, scarred and battered, American communities must not isolate veterans. Avoid the misplaced labels of mental illness. Listen. Help veterans heal on their own terms and at their own speed. With the right community support, with deep connections, our veterans will truly come home.

David Sutherland is a retired U.S. Army colonel and director of the Center for Military and Veterans Community Services (Dixon Center)

Paula J. Caplan is a Harvard University psychologist and author of “When Johnny and Jane Come Marching Home: How All of Us Can Help Veterans”

Read the article here: http://articles.philly.com/2013-02-10/news/37022089_1_department-of-veterans-affairs-million-veterans-war