By Kelly Patricia O’Meara

October 26, 2012

Law enforcement is in a unique position to collect data that may actually provide the most accurate information about the possible connection between psychotropic drugs and violence.

In an effort to summarize attempts by law enforcement to identify the reason(s) behind James Holmes killing 12 innocent people and injuring 58 others in an Aurora, Colo., movie theatre, one writer reports that “the search for an explanation has been elusive.” Maybe. But one could argue that the answers for such random, senseless violence isn’t so much “elusive,” as they are ignored and actually may lie in data that currently are in the hands of law enforcement.

Given the ever-increasing list of “shooters,” (Aurora, Virginia Tech, Columbine, etc.,) law enforcement has its hands full not only trying to keep the peace, but also attempting to determine the cause of the random violent behavior that plagues the nation’s cities. Because firearms are used in the execution of these violent acts, immediately attention is directed, or deflected, at instituting tougher gun control laws.

Conversely, the spotlight is rarely, if ever, directed at the very documentable fact that America is being “medicated” – having their brains chemically altered – at increasingly alarming rates. Recent analysis of pharmacy claims data by Medco Health Solutions, Inc., reveals that one in five American adults take at least one psychiatric drug and that the use of psychiatric drugs among adults grew 22 percent from 2001 and 2010. The data further revealed that 10 percent of men and a whopping 21 percent of adult women used antidepressants, adding $11.6 billion to pharmaceutical coffers.

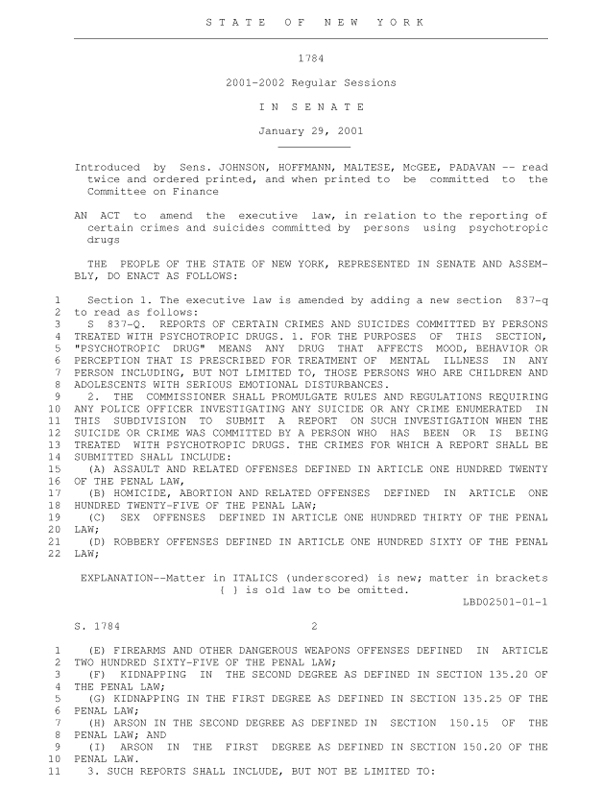

A bill introduced in New York in 2000 proposed police investigate psychiatric drug in all cases of violent crimes and suicides. Click image to read the bill

Antidepressants and other psychotropic drugs long have been the center of a raging debate about a connection between violence and psychiatric drug use. This debate came to a head when , in 2004, the Food and Drug Administration, FDA, added “black box” warnings (its most serious warnings) to most of the approved antidepressants because of suicidal thoughts reported in children taking the mind-altering drugs. And there are other reported adverse side effects associated with antidepressants including, but not limited to mania, (violent, abnormal behavior), hypomania, amnesia, manic reaction, psychotic reaction, delirium, delusion, hallucinations, hostility, psychosis and homicidal ideation.

Do any of these adverse reactions resemble the information provided to the public about James Holmes? Anyone who had viewed Holmes’ s first courtroom appearance would have to admit that, aside from his orange colored hair, he didn’t look quite “right.” Furthermore, Holmes apparently had been seeing at least three psychiatrists and, at a minimum, had been diagnosed with “Dysphoric Mania.” What the public has not been told is what cocktail of mind-altering drugs had his team of psychiatrists prescribed and at what levels.

A similar scenario recently unfolded with the shooting at the Atlanta World Changers Church International. Floyd Palmer, had been committed to a psychiatric hospital for a 2001 shooting at a mosque in Baltimore, Md. Having been released from that facility in 2005, Palmer made his way to Atlanta and unknown to the Atlanta church, the former psychiatric patient gained employment with the church as a maintenance man. As was the case in the 2001 shooting, earlier this month, Palmer inexplicably shot and killed a volunteer leading a prayer service at the megachurch. Again, the question must be raised: what mind-altering drugs had Palmer been prescribed?

It is precisely this information that may provide answers to Holmes’ deadly actions that to some seems so “elusive” and also to Palmer’s recent violence. The question that is conspicuously missing from the debate is whether Holmes’s seemingly uncharacteristic behavior, and Palmer’s not so uncharacteristic behavior, is the result of the mind-altering drugs they had been prescribed. In other words, did these men “go off” because of one or several of the known adverse reactions of psychiatric drugs?

To support the “psychiatric drugs cause violence” argument, a 2010 study from the Institute for Safe Medication Practices and published in the journal PloS One, and based on the FDA’s Adverse Event Reporting System, found that “adverse events are indeed associated with antidepressants and several other types of psychotropic medications.” The study “identified 31 drugs responsible for most of the FDA case reports of violence toward others, with antidepressants near the top of that list.”

Between 2004 and 2011, there were 12,755 reports to the U.S. FDA’s MedWatch system on psychiatric drugs causing violent side effects including: 1,231 cases of homicidal ideation/homicide, 2,795 cases of mania & 7,250 cases of aggression. Note that the FDA estimates that less than 1% of all serious events are ever reported to it, so the actual number of side effects occurring are most certainly higher.

While the FDA’s Adverse Event Reporting System is helpful, those data are based on self-reporting and many agree it represents a small percentage of the actual adverse events that occur. In fact, between 2004 and 2011, there were 12,755 reports to the U.S. FDA’s MedWatch system on psychiatric drugs causing violent side effects including: 1,231 cases of homicidal ideation/homicide, 2,795 cases of mania & 7,250 cases of aggression. Note that the FDA estimates that less than 1% of all serious events are ever reported to it, so the actual number of side effects occurring are most certainly higher.

Law enforcement, however, is in a unique position to collect data that may actually provide the most accurate information about the possible connection between psychotropic drugs and violence. Sue Todd, a retired Northern California detective, recalls that when she retired in 2001 “there was no training or focus on whether a suspect had been medicated with psychiatric drugs. The focus was on illegal drugs.” “Even today for the officer’s purposes,” explains Todd, “the arrest process is the same no matter what drugs they may be taking.”

The cop on the street may not be immediately concerned with whether a psychiatric drug plays a part in a violent act, but as the arrest process proceeds, law enforcement officials are on the frontline of data collection. “Currently,” says Todd, “the booking form that goes to reporting crime statistics on a national level could have a question about what medications are being taken by the suspect being booked.” “The Sheriff’s Departments usually are the primary housing authority,” explains Todd, “and they ask questions about the detainee’s medications.” “In light of the recent circumstances with people ‘going Postal,’ says Todd, “it seems reasonable that this medication information would be collected. It would be a perfect ground zero to analyze the data to see if there is any correlation.”

A veteran officer of the Los Angeles Police Department, who asked not to be identified, was in agreement with Todd’s assessment of past police practices and verified that detainee’s today must answer questions about any medications they may be taking. According to this source, “unlike arrests of the past, where people would tell us the drugs they were prescribed for diabetes, heart problems or blood pressure, today they’ll give us a shopping list of prescribed psychiatric medications.” “This data,” the source explains, “already is collected and is a gold mine of information that should be analyzed and the findings released to law enforcement, the government and the community.”

Just a cursory review of State and County police booking forms on the internet reveals that detainees most definitely are required to list any medications, including psychiatric medications, they may be taking. Like the FDA’s MedWatch, there would be no reason to collect personal identifying information and, therefore, no violation of HIPPA (federal law protecting individual health records) and no reason that this medication/offense data could not be collected and analyzed on a national level.

Setting up a national database that reflects the category of crime and what, if any, psychiatric drug the inmate may have been on at the time of arrest isn’t unheard of . In 2001, former New York State Senator, Owen H. Johnson, introduced a bill, S1784 that would effectively require law enforcement agencies in New York to collect data on certain violent crimes and what, if any, psychiatric drugs the offender may have been on during the commission of the crime.

Click the image to read the proposed NY Law which would have required police to investigate psychiatric drug use by any violent offenders

New York Senate Bill 1784, which passed the Senate, was very specific in its language as for the need for such legislation. “There is a large body of scientific research establishing a connection between violence and suicide and the use of psychotropic drugs in some cases. ”

The bill’s authors describe the research backing up the need for the legislation stating, “this research, which has been published in peer reviewed publications such as the American Journal of Psychiatry, the Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and the Journal of Forensic Science, has shown, among other things that: certain drugs can induce mania, some patients on psychotropic drugs have an increase in suicidal thoughts and/or violent behavior, self-injurious ideation or behavior is intensified, users of certain drugs can become aggressive or suffer hallucinations and/or suicidal thoughts and certain drugs can produce an acute psychotic reaction.”

While S1784 is remarkable in its insight and detail, it did not make it out of committee in the Assembly. But the seriousness of the problem has not lessened and New York is not the only state seriously looking into this matter.

A majority of legislatures already are focusing on the growing prescription drug abuse problems with their prospective states. According to the National Association of State Alcohol and Drug Abuse Directors (NASADAD) 32 states reported that state legislation pertaining to prescription drug abuse had been passed within the past five years and twenty-nine states currently have task forces designed to specifically address the problem of prescription drug abuse.

Clearly the reasons behind these tragic shootings don’t have to be “elusive.” The data are available, collected daily by law enforcement officials and may provide insight into these inexplicable acts of violence.

Kelly Patricia O’Meara is an award winning investigative reporter for the Washington Times, Insight Magazine, penning dozens of articles exposing the fraud of psychiatric diagnosis and the dangers of the psychiatric drugs – including her ground-breaking 1999 cover story, Guns & Doses, exposing the link between psychiatric drugs and acts of senseless violence. She is also the author of the highly acclaimed book, Psyched Out: How Psychiatry Sells Mental Illness and Pushes Pills that Kill. Prior to working as an investigative journalist, O’Meara spent sixteen years on Capitol Hill as a congressional staffer to four Members of Congress. She holds a B.S. in Political Science from the University of Maryland.

22 international drug regulatory warnings cite psychiatric drugs causing violent reactions including mania, psychosis, hostility, violence and homicide.

22 international drug regulatory warnings cite psychiatric drugs causing violent reactions including mania, psychosis, hostility, violence and homicide.