The Age

By Jill Stark

December 4, 2011

IT’S been branded a “dangerous public experiment” that could turn normal human experiences into an epidemic of mental illness with healthy people being drugged unnecessarily.

IT’S been branded a “dangerous public experiment” that could turn normal human experiences into an epidemic of mental illness with healthy people being drugged unnecessarily.

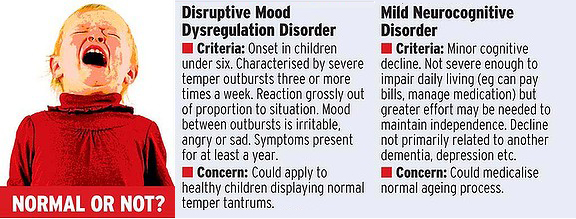

In radical changes to the way mental health conditions are diagnosed, what was once considered a child’s temper tantrum could be labelled ”disruptive mood dysregulation disorder”. If a widow grieves for more than a fortnight she might be diagnosed with ”major depressive disorder”.

If a mother in a custody battle tries to turn a child against the father, it might create ”parental alienation disorder”.

These are among new conditions proposed for the fifth edition of the psychiatrist’s bible, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), due to be finalised next year.

Some doctors in Australia are arguing the revised manual – used globally to diagnose mental disorders – is pathologising unhappiness.

The changes have also caused an international outcry, with the American Counselling Association, American Psychological Association, the British Psychological Society and others calling for the draft of the new edition to be independently reviewed.

They fear it is so inclusive, it risks labelling millions of healthy people as mentally ill.

”It’s such a narrow and limited view of human experience, to want to reduce every bit of suffering to medical diagnosis,” said Jon Jureidini, professor of psychiatry at the University of Adelaide. He said the changes would lead to increased prescribing.

The authors say ”misinformation” about the manual, produced by the American Psychiatric Association since 1952, is creating unnecessary fear and any inclusions will be based on robust scientific evidence. Psychiatrist Ian Hickie, director of Sydney University’s Brain and Mind Research Institute, rejects claims that the new manual would medicalise unhappiness. ”When people are in pain and suffering elsewhere we don’t say people are pathologising that. We say, let’s try and do the best we can to relieve that and get them back to function in the appropriate way,” Professor Hickie said.

The rift reflects division within the mental health community over a global rise in the use of antidepressants, stimulants and antipsychotics, with many clinicians critical of drugs with potentially serious side effects being favoured over more costly talk-based therapies. Others argue that medication can be life-saving where other therapies have failed. The inclusion of conditions such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and autism in previous DSM editions is believed to have contributed to increased prescribing.

In the new edition, the diagnosis threshold for some existing disorders is also being lowered so that

over the death of a loved one can qualify as a major depressive illness.

The authors of DSM-5, however, argue that a bereaved person who is suffering from major depression is currently ineligible for that diagnosis, preventing them from getting help if they need it.

”A broad range of evidence … shows that there are little to no systematic differences between individuals who develop a major depression in response to bereavement and in response to other severe stressors – such as being … raped … or the loss of your treasured job,” Dr Kenneth Kendler, a member of the DSM-5 mood disorders group, said.

The changes also mean children only have to display six of 13 possible symptoms for a diagnosis of ADHD, compared with six of nine in the previous manual.

”Under the new criteria it’s almost harder not to get diagnosed with ADHD than it is to get diagnosed with it,” Martin Whitely, a West Australian Labor MP and anti-ADHD medication campaigner, said. ”There were about 60,000 Australian children on ADHD medications in 2010 – a lot of money has gone into marketing and selling the disease.”

One of the manual’s biggest critics is the man who developed the last edition, American psychiatrist Allen Frances. He told The Sunday Age the fact that the authors of the new edition have described it as a ”living document” makes it a ”dangerous public health experiment”.

”The DSM-5 is used in real life-and-death decisions – it shouldn’t be a set of hypotheses to be tested,” he said. ”The worst outcome of this would be all these suggestions get included and a lot of people get medicine they don’t need. But an almost equally bad outcome would be that psychiatry gets so tarred by this aberration that people who really need psychiatry and need the medicine stop taking it.”

http://www.theage.com.au/national/psychiatry-bible-turns-sorrow-into-sickness-20111203-1ocmm.html