New Scientist

By Samantha Murphy

October 20, 2011

It is the tale that launched a thousand alter egos: the famous true story of “Sybil”, who endured years of torture at the hands of her sadistic mother and grew up into the meek, anxiety-ridden adult whose head was said to house 16 personalities.

It is the tale that launched a thousand alter egos: the famous true story of “Sybil”, who endured years of torture at the hands of her sadistic mother and grew up into the meek, anxiety-ridden adult whose head was said to house 16 personalities.

For many, she provided a startling introduction to a rare and intriguing condition: then known as multiple personality disorder (MPD), a disease of the mind affecting mostly women, in which a person hosts several vastly different personalities representing fractured aspects of a haunted past.

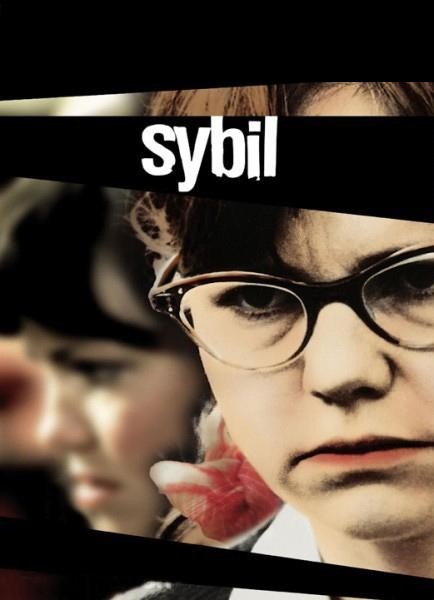

Luckily, with the help of her psychiatrist’s enduring dedication to her treatment – which included many punched-out office windows and late-night house calls – Sybil was finally able to come to terms with the other sides of herself and integrate them, triumphing over her disease. The tale made for a compelling book, Broadway show and an even more engaging movie in 1976 (and a less riveting remake in 2007). The book and film became instant classics, not to mention teaching tools for psychology students.

But according to investigative journalist Debbie Nathan, the story of Sybil has one big problem: it’s mostly bunk.

In Sybil Exposed, Nathan, famous for her exposés on “recovered memory syndrome”, goes through the story, claim by claim, with a fine-toothed comb. It’s a massive undertaking of research that teases apart fact from fiction to reveal an even more interesting and educational account of, not 16, but just three personalities: the author, Flora Schreiber, the psychiatrist, Cornelia Wilbur, and “Sybil”, Shirley Mason.

What Nathan found among the archives was “shocking but utterly absorbing”, she says. Mason’s 16 personalities had not appeared spontaneously as they do in the book and movie, but were “provoked over many years of rogue treatment that violated practically every ethical standard of practice for mental health practitioners”, she writes.

This is quite a firebomb to throw into a heated battle that started in the late 1990s and is still being fought today. The lines are drawn between whether MPD, since renamed dissociative identity disorder, exists as an artefact of post-traumatic stress disorder, as its own unique illness, or if it is merely the product of wishful, reinforcing therapy and willing clientele.

While the next edition of psychiatry’s bible, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, is in development, this is no small quibble.

Nathan uses direct quotes from the actual psychoanalysis session transcripts, excerpts from Mason’s diaries, and Schreiber’s author notes to provide fascinating insights into how these three women turned sickness and desire into a business.

When Wilbur, an ambitious female psychiatrist in a field packed with men, found Mason, an attention-starved and admiring patient, it was not long before they were engaged in a twisted parent-child kind of relationship. Nathan shows how Wilbur supplied her patient with attention and affection, and Mason eagerly performed whatever dance seemed to please Wilbur most.

At one point Mason wrote a letter attempting to confess to Wilbur that she had invented these personalities. She also asked that they stop “demonizing” her mother – who Wilbur had cast as a vicious abuser but who Nathan suggests was just religiously strict and emotionally unpredictable. Wilbur dismissed the letter as a defence mechanism, and her patient, desperate not to lose the doctor’s interest, continued the charade. Soon after, the two women met Schreiber, who spun their story into the profitable and sexy legend we know today.

Sybil remains a good book and movie, but perhaps Nathan’s version of the story is the one worth telling in classrooms. Though it is the less sensational tale, it is a cautionary one. It is a solemn reminder of why mistrust plagues the mental health field, and why we must always be careful to pin down the facts, and leave it to fiction to get carried away with the story.

http://www.newscientist.com/blogs/culturelab/2011/10/was-sybil-a-psychiatrists-creation.html