The Sydney Morning Herald – September 13, 2011

by Tanveer Ahmed

"Mental health possesses a built-in capacity for abuse that is greater than in other areas of medicine."

Imagine a tribunal where the public could challenge clinical decisions by neurosurgeons or cardiologists. It would be ridiculous. But mental health is different. Unlike other medical specialties, it resembles law or politics: fields where subtle variations in the interpretation of a word can alter the entire trajectory of a patient’s treatment.

That’s why the right to appeal clinical decisions by mental health professionals through a tribunal, announced recently by the NSW government, met with public approval. Mental health possesses a built-in capacity for abuse that is greater than in other areas of medicine. A patient’s psychiatric diagnosis has enormous cultural power in many other fields, from the marketing of antidepressant medications, to general practice, disability claims and legal proceedings.

The contestable nature of mental health is also why there is a constant battle to keep it free from politics. Some of the 20th century’s most despotic regimes used mental health to oppress opponents, coining disorders such as ”delusions of capitalism” in the Soviet Union or ”politically paranoid” in China. But psychiatry has a way of becoming a political football in public discourse regardless of how authoritarian or democratic the society.

Today it is increasingly a tool of progressive politics, used to highlight the human pain apparently caused by harsh policies. In the case of asylum seekers, for example, any emotional distress is automatically viewed through the lens of mental health. Resilient individuals who have escaped harsh circumstances and coped with far-reaching travel are suddenly classified as fragile, undone by bureaucratic delay and limited incarceration. There is no doubt mental illness exists among asylum seekers, but its prevalence is vastly overstated.

In one of the more farcical applications of psychiatry to political debates, a report this month linked inaction on climate change to the possibility of worsening mental health. Released by the Climate Institute, it suggested that increasing natural disasters might be linked to climate change, which might lead to increased costs in mental healthcare. The evidence for every link was slight at best, yet the novelty of the report ensured widespread attention.

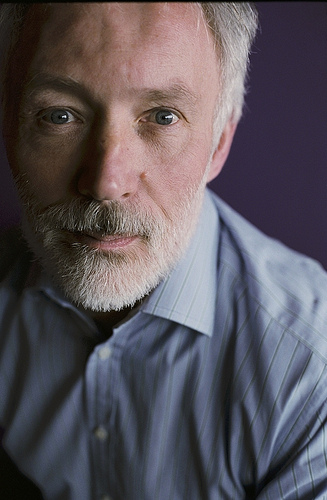

It was launched by Professor Ian Hickie, who has been rightly recognised for giving mental health a greater profile, but who has also played politics to do so.

Hickie has done more than any other clinician to promote tick-a-box diagnosis, particularly among general practitioners, who now regularly prescribe antidepressants through questionnaires alone.

"It is disingenuous to suggest, as McGorry has done, that there is no conflict of interest because their organisations are non-profit."

With former Australian of the Year Professor Patrick McGorry, Hickie has made overblown claims about the prevalence of mental health. It is disingenuous to suggest, as McGorry has done, that there is no conflict of interest because their organisations are non-profit. Their bodies shared in $2.2 billion of funding in the federal budget. Their exorbitant claims – such as one in four people will suffer mental illness – are indicative of a blurring of the lines between illness and normal, human responses to adversity.

Another good example of the uneasy relationship between politics and mental health – and how one can colour the other – is the former Victorian premier Jeff Kennett, a tireless campaigner in raising awareness for depression who openly admits he uses the term not in its medical context, but as a synonym for emotional distress.

The fiercest critics of this modern therapeutic culture in Western societies have argued that the decline of the political left is at the heart of the trend – in particular, the collapse of any ambition for social change.

Having given up on the notion that human beings could collectively change the world, the argument goes, the left has instead focused on people adapting to their circumstances.