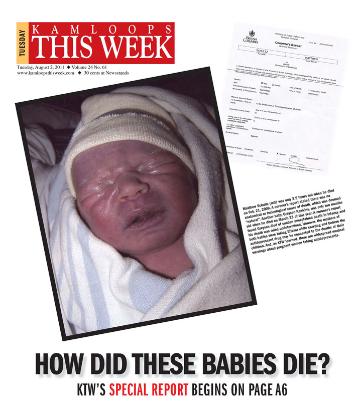

Matthew Schultz was only 2.5 hours old when he died on Feb. 21, 2009. A coroner’s report stated there was no anatomical or toxicological cause of death, which was deemed “natural”. Another baby, Greyson Rawkins, was only two months old when he died on March 23 of this year. A coroner’s report found Greyson died of sudden unexplained death in infancy and his death was ruled undetermined. However, the mothers of both babies were taking Effexor while carrying and believe the antidepressant drug may be connected to the deaths of their children. And, as KTW learned, there are widespread medical warnings about pregnant women taking antidepressants.

Two hours is not a lot of time, but for little Matthew Schultz, it was his entire life.

One moment, Amery Schultz held Matthew in his arms. The next moment, his child was dead.

As the Merritt family struggled to deal with their grief, two years later and 45 minutes away in Kamloops, another family would be shattered by the sudden loss of a newborn.

Greyson Maxwell Rawkins was found one morning by his mother, cold and unresponsive.

The two-month old was dead.

Unlike most sudden-infant deaths, which go largely unexplained, both families believe they know exactly what killed their sons — an antidepressant called Effexor.

Matthew was born on February 21, 2009, at 2:21 a.m. at Royal Inland Hospital.

Right from birth, the newborn had poor colouring and trouble breathing.

Schultz said he and wife Christiane argued with medical staff at the hospital about Matthew’s symptoms, only to be told they was normal.

An hour later, alone in the hospital room, Amery held Matthew in his arms.

He was gently rocking his fifth child to sleep and noted the baby’s lips were a bit purple.

Matthew fell asleep in his father’s lap.

Moments later, a nurse came into the room and noticed the new born was pale and unresponsive.

Matthew was in complete respiratory and cardiac arrest.

Medical staff were unable to revive him and he was pronounced dead an hour later.

“Losing your child — you can’t explain it,” Amery said.

“It tears a hole in your heart that will never heal.”

The B.C. Coroners Service listed Matthew’s death as natural — as far as the coroner was concerned, it was a case of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS).

However, the Schultzes were not convinced.

The couple started to do their own research and were dismayed by what they found.

Christiane had been taking the antidepressant Effexor, also known by its clinical name venlafaxine, for years prior to Matthew’s birth and during pregnancy.

Three previous children were also exposed to the drug.

Unbeknownst to the couple, venlafaxine had been under a Health Canada warning since 2004.

The government agency had advised that newborns may be adversely affected when pregnant women take a specific group of antidepressants during the third trimester of pregnancy.

The list included venlafaxine.

The Schultzes said their family doctor never told them about the possible risks of taking the drug during pregnancy.

“I asked every pregnancy, ‘Should I get off of these?’” Christiane said.

“But I was told, ‘No, they’re fine, they’re perfectly safe.’”

Convinced Effexor contributed to Matthew’s death, the family awaited the final report from the coroner, hoping to get some answers as to the cause of their son’s death.

They were also hoping the coroner would make recommendations so other families wouldn’t suffer through a similar loss.

But the report, which the Schultzes received on the two-year anniversary of Matthew’s short life and death, surprised and angered the family.

It made no recommendations and found no cause of death.

According to the coroner’s report, a detailed autopsy on Matthew showed no anatomic cause of death, but the possibility was raised of venlafaxine exposure being a contributing factor.

Brain-tissue samples were sent to a research facility in the U.S. for examination to determine if there was an underlying susceptibility to the class of antidepressants.

But the report noted it was unclear how prenatal exposure to Effexor might have contributed to Matthew’s death, if at all.

The report concluded the significance of the exposure to venlafaxine in utero is unknown and made no recommendations.

“At best, I can’t bring my son back,” Amery said.

“But to call his death natural, certainly it’s not.”

He argued the coroners office has ignored what he considers overwhelming evidence the drug played a role in his son’s death.

The report itself listed exposure to venlafaxine under the category of other conditions contributing to death.

Physician and coroner Karla Pederson, with the B.C. Coroner’s Service, looked over the results of the report and is satisfied the office went to great lengths to find the cause of death.

“We are not making a presumption that we know what caused the death of this child, because we do not know,” she said.

When asked if the coroners service is concerned about the use of antidepressants during pregnancy, Pederson noted the drugs are used by thousands, if not millions, of pregnant women around the world without resulting in infant death.

Greyson Rawkins was born on Jan. 24, 2011, at RIH.

Like Matthew Schultz, little Greyson had trouble breathing at birth and spent five days in the hospital before he could go home for the first time.

“He was just different from my first,” said Greyson’s mother, Nicole Rawkins, who noted her second child weighed less and slept much more than her daughter, Layla, now three years old.

During her entire pregnancy, Rawkins said she was taking a prescribed 450-milligram daily dose of Effexor to help her depression.

It was more than five times the amount she took during her first pregnancy.

The 31-year-old Rawkins was also taking another drug called Seroquel, between 100 and 150 milligrams a day, which is used to treat bipolar depression.

She said her doctor never told her of the risks.

After two months, though, Greyson appeared to be doing well.

That was until the evening of March 22 of this year.

Rawkins put Greyson to sleep in his bassinet, in the same room with her and her boyfriend.

But the two-month old was being fussy, so mom brought him into her bed for nursing.

They fell asleep, with Greyson lying on the edge of the bed with his mom.

At around 4 a.m., Greyson’s older sister decided to climb into bed, while Rawkins’ boyfriend moved to a couch.

Five hours later, Rawkins awoke to find her son cold and unresponsive.

“I shook him a bit, but he was floppy,” she recalled.

Emergency services was dispatched, but it was too late.

Greyson was dead.

Rawkins thought she had accidently killed her baby, but that wasn’t the case.

A coroner’s report released at the end of June listed the death as undetermined and classified it as SIDS.

As in the Schultzes’ case, the autopsy noted Effexor and Seroquel as risk factors for SIDS in the case, but added it could not be determined by a pathological exam.

An autopsy on Greyson also stated the respiratory complications at birth were considered likely secondary to withdrawal effects from utero exposure to venlafaxine.

Despite the findings, Rawkins said the blame in Greyson’s death has fallen on her shoulders.

“I wasn’t allowed to grieve because everyone was watching me,” she said.

After getting in contact with the Schultz family and sharing their stories, Rawkins is also certain the antidepressants she had taken for months played a role in Greyson’s death.

The two mothers have been carrying around their own guilt because they unwittingly exposed their children to the drug.

“Every day I look at them and I did that to them because I didn’t look up the safety of the drug,” said Christiane.

“Every day is guilt.”