The Daily Mail – June 13, 2011

by Sue Reid

“This doctor said at the inquest my son had a chemical imbalance in his brain. I asked him: “How do you know? Did you take chemicals from his brain? ‘He told me it was a theory. So based on a theory — and seeing my son five times at the most — he decided to put him on this drug, Ritalin, which is as powerful as cocaine.” – Darren Hucknall

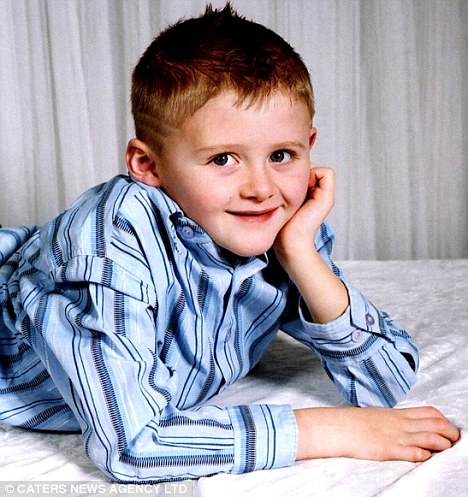

Captured in a family video, Harry Hucknall gives a cheeky grin before whizzing off down the street on his new bike. His father, Darren, will never forget the moment — when Harry was seven — and often watches the scene again and again.

It is a precious memory of Harry who, one Sunday evening in September last year, kissed his mother Jane and older brother, David, goodnight before going upstairs to his bedroom and locking the door. He then hanged himself with a belt from his bunk bed.

He was ten years old.

His father blames Harry’s death on two ‘mind-altering’ drugs that his son had been prescribed by a psychiatrist to cure his boisterous behaviour and low spirits.

An inquest was told in April that the boy had more drugs in his body than the normal level for adults suffering from the same problems.

Now, a distraught Mr Hucknall is to make a formal complaint to the NHS for prescribing his son Ritalin, a cocaine-like stimulant which, paradoxically, is said to calm down a child, and Prozac, a powerful antidepressant.

‘When I was growing up there were lots of kids like Harry — a bit over-active, a bit naughty, who didn’t always do as they were told. Now they are branded with a complaint called attention deficit hyperactivity disorder,’ says the computer engineer at his semi-detached house on the outskirts of Barrow-in-Furness, Cumbria.

‘What is it? What has changed? Is there some weird disease in the air? Harry was just a normal little boy. But because we live in 2011 he, and many other kids, are on tablets.

‘It seems nearly every child has suddenly developed this ADHD. What a load of nonsense. It’s an easy get-out for parents and schools who can’t control children.’

Mr Hucknall is obviously grieving for Harry, and his words are spoken with anger. But they are close to the truth. Earlier this year, this paper revealed that 661,000 prescriptions are dished out annually in Britain to treat childhood ADHD — double the figure of five years ago.

Coroner: An inquest was told in April that the boy had more drugs in his body than the normal level for adults suffering from the same problems

These medicines are being given to very young children — one aged just 15 months, according to our investigations — despite official guidelines from the manufacturer and the fact that the UK’s National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) prohibits their use for those under six.

Last week, educational psychologist David Traxson told me he suspects that in the West Midlands at least 100 three, four and five-year-olds are on Ritalin or similar drugs. If this is replicated around the country — as is likely — the number will run into thousands.

‘These young children are taking powerful, potentially addictive drugs and no one knows what will happen to their brains in the future,’ he warned.

The Association of Educational Psychologists last week demanded a national review into the use of Ritalin and similar drugs on children.

General Secretary Kate Fallon said: ‘The danger is that we rely on this “quick fix” for children with conditions such as ADHD, which frequently means a prescription for Ritalin.

‘We have significant concerns that the neurological impact of these drugs on the developing brains of children has not been fully researched. The potential damage they could cause needs further investigation.’

In America (where the term ADHD was first created 50 years ago), one in five children is diagnosed as having a hyperactivity disorder and is on Ritalin or a similar drug

The psychologists’ call was backed by the National Union of Teachers, whose members have to cope with the huge rise in pupils being dosed with ADHD drugs — which act on the central nervous system to change a child’s behaviour.

In some state primary classrooms, one in ten pupils is on Ritalin pills, which have to be handed out by teachers at lunch or break times. In one junior school of 389 children in the South-East, no fewer than 80 pupils — more than 20 per cent — are on the medication.

It is a phenomenon across Britain, affecting families in every income bracket. The area with the highest proportion of children receiving the drug is the Wirral, a wealthy part of Cheshire which is home to millionaire footballers and business executives.

Meanwhile, sceptics question the very existence of ADHD as an illness. There is no recognised test for it. A diagnosis is made by a psychiatrist or paediatrician merely by watching a child’s behaviour.

Some of the doubters argue the condition is really a politically correct creation, conjured up by the medical world for a child who finds it difficult to sit still or concentrate thanks to a combination of a fast-food diet, late nights and lack of exercise.

It’s easier for the medical world and its political masters, of course, to diagnose a syndrome rather than deal with the real causes.

Another worrying factor is that the parents of children receiving drugs for ADHD immediately become eligible for an array of generous state benefits, including a carer’s allowance and child-disability allowance, which can total thousands a year.

For instance, one family in the West Midlands has two children receiving medication for ADHD. They get £600 a month in disability allowances for each of the two children who have been diagnosed with the ailment.

A third child is being examined by psychologists to see if he is also a sufferer. If he is diagnosed, the family’s annual haul from the state will be £21,600 tax free.

No wonder thousands of families happily agree with child psychiatrists when they are told their son or daughter needs medicine to ‘cure’ their hyperactive behaviour.

Gwynedd Lloyd, an education researcher at Edinburgh University, has explained her doubts. ‘You can’t do a blood test to see if a child has ADHD. It is diagnosed by ticking a behaviour checklist — getting out of your seat and running about is an example. Half the kids in a school would qualify under these sorts of criteria.’

And, it appears, a lot of them do. In the four years to 2010, there was a 65 per cent increase in NHS spending on drugs to treat childhood ADHD, with a cost to the taxpayer of £31million annually. This does not take into account thousands of prescriptions paid for by parents who take their children to private doctors.

In America (where the term ADHD was first created 50 years ago), one in five children is diagnosed as having a hyperactivity disorder and is on Ritalin or a similar drug.

It is predicted that unless the craze for drugging children is not stopped in the UK, one in seven pupils will soon be diagnosed with the condition in many parts of the country, as is already the case in places such as the Wirral.

Meanwhile, the side-effects of the ADHD treatments are legion. Ritalin is a Class B drug, which is banned for recreational use. It was invented in the Fifties in the U.S. to combat the effects of illegal drug overdoses.

Alarmingly, it can stunt growth (doctors are asked to regularly monitor a young patient’s height and weight), while making children prone to heart problems, depression and insomnia.

At least 11 deaths of children while taking Ritalin have been reported to the UK’s Medicines and Healthcare Products’ Regulatory Agency since the drug became available 20 years ago. The official causes of nine of the deaths included heart conditions, respiratory problems and brain diseases. Significantly, two of the children ended their own lives just like Harry Hucknall.

Home Secretary Theresa May has said that enough is enough. As the Shadow Leader of the House of Commons before the last election, she warned of the dangers of the ADHD drugs. ‘They are powerful prescription drugs and we don’t know what their long-term effects on a child will be.’

She related to Parliament the story of a six-year-old on Ritalin. ‘He experienced low moods and marked depression and tried to throw himself out of a window within two months of starting treatment. He only recovered once the drug had been withdrawn.’

Sadly, Harry Hucknall never had the chance to stop taking Ritalin, or the antidepressant Prozac. Now his father is asking difficult questions about why his son died. On the fateful weekend last September, Harry was staying at the home in Dalton-in-Furness of his mother, Jane White, 33, his brother David, and his two step-siblings.

He would spend every other weekend and one day during the week with his father, who parted amicably from Jane when Harry was three.

Early last year, child psychiatrist Mr Sumitra Srivastava had prescribed Harry with Prozac for depression, and Ritalin for hyperactivity. He was having difficulty concentrating at school, was being bullied by classmates, and had told his parents he was feeling unhappy.

At an inquest in April, the coroner Ian Smith declared that Mr Srivastava had acted appropriately, but warned that doctors should be extremely careful what they prescribed to ten-year-old boys.

The coroner ruled out a deliberate suicide, but said that the influence of Ritalin and Prozac could not be excluded as a factor in Harry’s death. ‘What a child with ADHD is prescribed by his doctor is mind-altering drugs of a powerful nature,’ he added.

But Harry’s father believes drugs had a huge part to play in the tragedy. ‘Harry was put on Prozac first, and without my knowledge,’ he told me. ‘I only found out about it when he came to stay for the weekend and his mother told me what dose to give him: one in the morning and one at night. “Are you crazy?” I asked her. “That’s an antidepressant.”

‘I can go to work every day and pay for my child’s keep, but it seems I have little say when it comes to things like the authorities deciding to give my son drugs.’ At first, Mr Hucknall refused to give Harry the pills. But Harry’s mother said that if he didn’t dose his son, the child would not be allowed to visit him. She said the doctors had told her Prozac would stop Harry being depressed.

‘I reluctantly agreed. I wanted to see Harry,’ remembers 37-year-old Mr Hucknall. ‘Later, I went with Harry’s mother to see the psychiatrist. I insisted on going along to tell him that I did not want Harry on any drugs whatsoever.

‘While I was there, he said Harry was going to be put on Ritalin as well. I said I did not want him on more drugs. I didn’t want him on any at all.

‘I had never heard of Ritalin. I was told it was to help his concentration. I was never told a side-effect of Ritalin is depression. But the doctor said that if Harry took the Ritalin he would be off everything and drug free within a month.’

Mr Hucknall believed him, although this scenario was very unlikely. Most children remain on ADHD drugs for years. ‘In the end I agreed, because I thought I was doing the right thing. The next thing I know, a month or two later, there was a knock on my door and two police officers were telling me my son had hanged himself,’ he says.

‘He was just a kid. There was nothing wrong with him. He may have had some problems, but they were overstated.

‘A lot of things that Harry’s mum complained about in terms of his behaviour, he did not do here. How can you have ADHD in one place and not in another?

‘I think Harry might have been playing up a bit by attention- seeking because there were three other children in the family.

‘I admit there were a couple of times I forgot to give him his tablets. To me, he seemed quiet and subdued when he was on them.

‘I would have happily thrown them in the bin. Harry just took them, of course. He was a kid and he did as he was told.’

An emotional Mr Hucknall continues: ‘I think ADHD is a disease invented by drug companies. Nobody ever died of ADHD and it didn’t existed once upon a time. It’s too easy to hand out tablets. They are being over-prescribed to children.

‘A perfectly normal kid isn’t allowed to grow up without interference these days. I’m angry about what has happened because I have lost my son.

‘At the school meetings about Harry, his teachers said he was quiet. My son had just recently moved house and been put into a new school, where he didn’t know anybody. What did they expect?

‘Another teacher said Harry didn’t laugh at his jokes. I asked Harry about that. He told me they weren’t very funny.’

Mr Hucknall believes his son was ‘inappropriately medicated’ and has asked Independent Complaints’ Advocacy Service (ICAS) — which supports those wishing to complain about the NHS — to take on the case.

At the inquest, Mr Hucknall also took the chance to challenge Mr Srivastava again about why he had put Harry on drugs. ‘This doctor said at the inquest my son had a chemical inbalance in his brain. I asked him: “How do you know? Did you take chemicals from his brain?”

‘He told me it was a theory. So based on a theory — and seeing my son five times at the most — he decided to put him on this drug, Ritalin, which is as powerful as cocaine.

‘Harry ended up taking two drugs that work against each other — the Prozac that fights depression and the Ritalin that can cause it. How can that be right?’