Financial Times

By Andrew Jack

March 8, 2011

Stefan Kruszewski, a US psychiatrist who has been a whistleblower against pharma companies in three recent cases that resulted in settlements, warns that the legacy of the past will generate yet more pain. “Some companies have got better,” he says. “But there is more to come out.”

When Daniel Carlat, a psychiatrist in Massachusetts, was flown to New York with his wife by Wyeth, the “training” weekend he attended in a luxury hotel was topped off with a Broadway show. It was early 2001 and he had just agreed to the US pharmaceuticals company’s proposal that he give talks to doctors about its antidepressant Effexor.

During the following year, he was regularly paid fees of $750 a time to drive to “lunch and learn” sessions where he would speak for 10 minutes to emphasise the drug’s advantages to fellow doctors, using slides prepared by the company. “It seemed like a win-win,” he recalls. “I was prescribing it, educating doctors and making some money.”

But within a few months, he became disillusioned with his co-option as a marketing representative. He was selectively presenting clinical data that put the drug in a positive light to physicians who had been targeted by the company through “data mining” techniques that identified their individual prescription patterns.

Dr Carlat has spoken out as part of a growing backlash against such aggressive marketing tactics, which are leading to significant changes in the relationship between doctors and drug companies. But even as pharmaceuticals executives argue that such problems belong to the past and were always exaggerated, they are bracing for both intensifying penalties and calls for further reform.

“In some ways, our industry lost its way and failed to fully appreciate the evolving expectations of our stakeholders,” Deirdre Connelly, head of North American operations at GlaxoSmithKline, told a conference in January. While playing down the extent of the problem, she conceded: “No matter the reasons, at the end of the day, we must regain the public’s trust.”

“In some ways, our industry lost its way and failed to fully appreciate the evolving expectations of our stakeholders,” Deirdre Connelly, head of North American operations at GlaxoSmithKline, told a conference in January. While playing down the extent of the problem, she conceded: “No matter the reasons, at the end of the day, we must regain the public’s trust.”

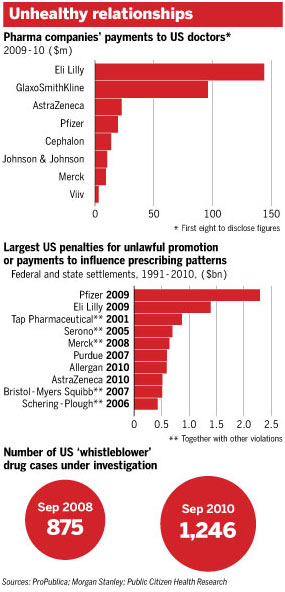

Her comments came as the UK-based company put aside provisions of £2.2bn ($3.6bn), largely to cover a settlement under negotiation with the US district attorney’s office for Colorado over sales and promotional practices between 1997 and 2004 for drugs including its antidepressants Paxil and Wellbutrin. A report in January by Morgan Stanley, the investment bank, predicted a surge in litigation, including against GSK, as still undisclosed “whistleblower” lawsuits and regulatory settlements translate into claims totalling billions of dollars for the industry in the coming months.

At the heart of the problem is a wide-ranging, cosy and opaque relationship between companies and physicians – one that often includes money or other benefits changing hands. For most in the industry, such links are essential to understanding diseases and patient needs, developing effective medicines and providing education on them to prescribers.

US authorities have taken the lead, investigating practices used in other countries as well as at home. Authorities elsewhere, including in the UK, France and Italy, have also been scrutinising arrangements.

Chris Viehbacher, head of Sanofi-Aventis, the French drugmaker, rejects the suggestion that payments need cause insuperable problems. “Doctors are professionals and I have every confidence in their judgment,” he says, arguing that payments from companies need not undermine the integrity of prescribers.

Yet others argue that payments to doctors have at times resulted in the prescription of medicines to patients who do not stand to benefit, risking suboptimal or even dangerous treatment and substantial and unnecessary costs to health systems.

“The industry has made important steps to clean up its act, but more needs to be done,” says Richard Horton, editor of The Lancet, the medical journal. He chaired a working party at the UK’s Royal College of Physicians two years ago that launched recommendations to rebalance the relationship between the industry, academia and the taxpayer-funded National Health Service. In the face of a lack of consensus and practical difficulties, many have yet to be implemented.

He and others say questionable links between doctors and industry reached their apogee in the US at the start of the millennium, when fierce competition among companies at a time of slowing innovation resulted in the creation of a slew of “me too” drugs, often with little advantage over existing treatments. Pressure from increasingly aggressive makers of low-cost generic versions of out-of-patent proprietary products heightened the urgency of maximising sales. Companies were spending heavily on media advertisements – often including celebrity endorsements – to persuade patients to lobby doctors for prescriptions of their products.

Above all, a wave of takeovers spurred by falling productivity left newly expanded groups such as Pfizer with thousands of sales “reps”, often recruited more for their charm than their medical expertise, charged with visiting doctors to persuade them to prescribe their drugs. This created an “arms race” among leading companies, often with barely distinguishable products.

One tool used in the US was “sampling”, whereby reps would leave free supplies of their often costly drugs with doctors, who were able to hand them out to patients without medical insurance. They also paid for physicians’ meals and even petrol.

In Europe and most other industrialised regions, direct-to-consumer advertising of prescription medicines is typically banned or tightly controlled, and free samples are less relevant in markets where drugs are largely paid for by governments.

Yet close links between sales reps and doctors have been widespread – and not always limited to small gifts such as pens, notepads and coffee mugs. There have also been allegations of significant payments, some of which are under scrutiny by federal investigators focusing on the overseas activities of companies operating in the US.

In the UK, US-based Abbott Laboratories was severely reprimanded by the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry in 2006 after reps took doctors to Wimbledon matches, greyhound races and a lap-dancing club. Two years later, Swiss-based Roche suffered the same fate after encouraging the sale of weight-loss pills to individuals in private slimming clinics not qualified to prescribe.

. . .

Practising doctors are required by their own professional bodies to participate in “continuing medical education” sessions to keep up to date. But speakers and themes can be influenced by drugmakers. Often flown business class with their spouses to resorts in exotic locations, doctors around the world attend scientific conferences where companies hold “satellite” sessions presenting their products in a favourable light.

While Dr Carlat participated in such “speaker bureaus”, other “key opinion leaders” were paid as consultants for a variety of services. Those included advice on the design and writing up of clinical drug trials and adding their names and credibility to articles ghost-written by specialist authors hired by the companies.

A series of studies has demonstrated that industry-sponsored trials published in medical journals – a cornerstone of marketing to doctors – generally favour their drugs. Trials with less promising results are not generally published. This can distort the true picture of risks and benefits of medicines.

The full extent of such marketing activities and any distortion of prescribing practices is unclear. But “sunshine” legislation introduced as part of US President Barack Obama’s healthcare reforms is beginning to reveal the amount companies have been willing to spend. According to an analysis by ProPublica, an investigative journalism agency, the first eight companies to disclose their spending paid a total of $320m in 2009-10 to 18,000 doctors, the top 10 of whom received more than $250,000 each.

Such transparency is itself accelerating reform. Companies – some forced by legal settlements, others persuaded by the requirements of government funders and medical journals – are making details of their clinical studies available on public websites, allowing scrutiny by independent researchers. GSK this year changed its payment system for reps, hiring and assessing them based on medical expertise and removing commissions linked directly to sales.

Organisations including Britain’s ABPI, its Swedish counterpart Lif, and Efpia, the European Union-wide trade body for the sector, have introduced ever tougher codes of conduct that have restricted gifts, drug samples, entertainment and travel. In the US, the independent Institute of Medicine has called for far more aggressive measures to control continuing medical education, in order to put content at arm’s length from drug companies. The National Institutes of Health, the US federal research funder, is revising its conflict of interest codes for grant recipients, and many medical schools have taken similar steps to clamp down on industry influence on faculty members.

But such measures have proved partial. Disclosure of clinical trial results remains patchy, and pledges to publish payments to doctors in Europe are less comprehensive than those in the US. The ethics code of Phrma, the US trade grouping, has no enforcement mechanism. Ifpma, the international body, has only ever considered – and then rejected – four complaints against companies.

Susan Chimonas, of New York’s Columbia University, says the medical profession must take more responsibility. She highlights a recent study that found the majority of US medical schools had weak or non-existent conflict of interest guidelines on payments to their faculty. “It takes two to tango,” she argues. “Industry is behaving the way industry is expected to in a capitalist system, but the medical profession has lost its way. Prescribers are willing partners.”

In the UK Des Spence, a Glasgow doctor who founded a national chapter of the No Free Lunch movement, which rejects drug company hospitality, points out that the NHS is supposed to provide registers of payments to doctors, but few disclosures have been made. The General Medical Council, the profession’s regulator, has shown little interest.

. . .

The greatest pressure for reform has come from governments and health insurers. A growing trend towards rigorous and continuing comparative data on drugs’ safety, efficacy and cost-effectiveness is shifting prescription powers from individual doctors to technical organisations such as the UK’s National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence.

The result has been a cull in tens of thousands of drug reps in the industrialised world in the past few years, although their numbers have been growing in the less-regulated emerging markets to which the pharmaceuticals companies are increasingly turning. If some of the more egregious payments to doctors are on the wane, that leaves more subtle issues such as the independence of continuing medical education. If the drug industry pulls back, either individual doctors or their employers will have to provide funding instead.

With austerity measures squeezing government health spending in many countries, and UK changes giving more powers to family doctors, the solution will not be easy. Stefan Kruszewski, a US psychiatrist who has been a whistleblower against pharma companies in three recent cases that resulted in settlements, warns that the legacy of the past will generate yet more pain. “Some companies have got better,” he says. “But there is more to come out.”

Read the rest of the article here:

http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/ae7099a0-49bc-11e0-acf0-00144feab49a.html#axzz1G80Pn69u