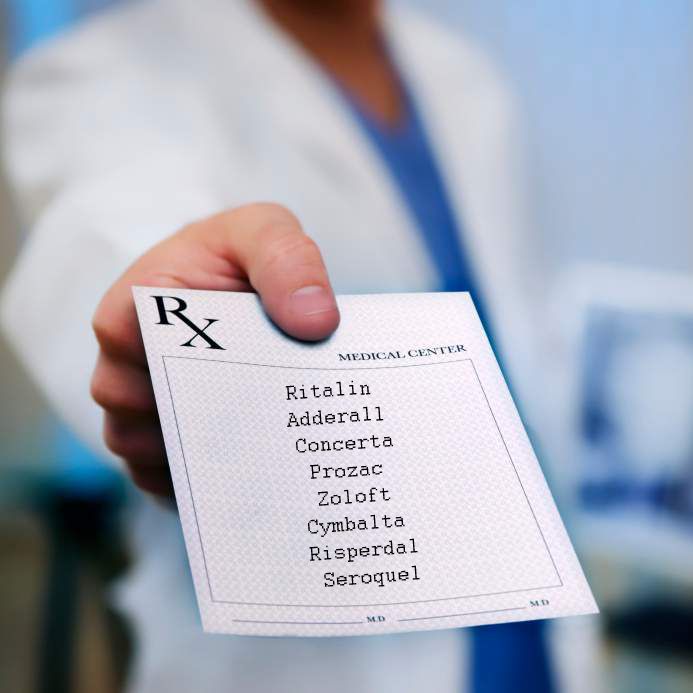

Note from CCHR: One of the most common misconceptions about psychiatry is that they help patients navigate through life’s problems with conversation or dialogue. While that may make for interesting drama on The Soprano’s —its a far cry from real life psychiatry. Psychiatrists are drug pushers. They diagnose and drug, plain and simple. And they diagnose patients without the aid of any medical tests for the simple reason, there aren’t any. Psychiatry as a profession must maintain that all life’s problems are the result of brain malfunction, otherwise known as the biological model of mental disorders as “disease” in order to maintain their partnership with Big Pharma that garners billions in government funding and convinces the public to take drugs. And what a brilliant marketing campaign it has been; the public, legislators, governments and the press have all been convinced that mental disorders are medical conditions, requiring drugs to “treat” them, despite the fact there is not one chemical imbalance or blood test, MRI or X-ray to prove this theory. Now that, is what billions of dollars spent on lobbyists, pharmaceutical front groups like the National Alliance for Mental Illness (NAMI) and paid psychiatric experts can buy you. However, it also stands to reason that the psychiatric industry cannot really employ or endorse talk therapy, because they would be admitting that life’s problems are not the result of chemically imbalanced or faulty brains, that people can get better without the use of mind-altering and life-threatening drugs. So while the article below has some good points, it misses a big one— the psychiatric industry is the one that sold insurance companies, governments and the general public on the fraudulent “mental disorders are biological/medical conditions” marketing campaign that is the foundation upon which their $82 billion-dollar-a-year drug industry rests. For more information watch Dr. Niall McLaren, a practicing psychiatrist for 22 years, explaining how psychiatry’s reliance on the biological model of mental disorder as disease and how the facts could unravel the entire profession

Note from CCHR: One of the most common misconceptions about psychiatry is that they help patients navigate through life’s problems with conversation or dialogue. While that may make for interesting drama on The Soprano’s —its a far cry from real life psychiatry. Psychiatrists are drug pushers. They diagnose and drug, plain and simple. And they diagnose patients without the aid of any medical tests for the simple reason, there aren’t any. Psychiatry as a profession must maintain that all life’s problems are the result of brain malfunction, otherwise known as the biological model of mental disorders as “disease” in order to maintain their partnership with Big Pharma that garners billions in government funding and convinces the public to take drugs. And what a brilliant marketing campaign it has been; the public, legislators, governments and the press have all been convinced that mental disorders are medical conditions, requiring drugs to “treat” them, despite the fact there is not one chemical imbalance or blood test, MRI or X-ray to prove this theory. Now that, is what billions of dollars spent on lobbyists, pharmaceutical front groups like the National Alliance for Mental Illness (NAMI) and paid psychiatric experts can buy you. However, it also stands to reason that the psychiatric industry cannot really employ or endorse talk therapy, because they would be admitting that life’s problems are not the result of chemically imbalanced or faulty brains, that people can get better without the use of mind-altering and life-threatening drugs. So while the article below has some good points, it misses a big one— the psychiatric industry is the one that sold insurance companies, governments and the general public on the fraudulent “mental disorders are biological/medical conditions” marketing campaign that is the foundation upon which their $82 billion-dollar-a-year drug industry rests. For more information watch Dr. Niall McLaren, a practicing psychiatrist for 22 years, explaining how psychiatry’s reliance on the biological model of mental disorder as disease and how the facts could unravel the entire profession

Or read Psychiatric Disorders

Talk Therapy Doesn’t Pay, So Psychiatry Turns Instead to Drug Therapy

New York Times

by Gardiner Harris, March 5, 2011

DOYLESTOWN, Pa. — Alone with his psychiatrist, the patient confided that his newborn had serious health problems, his distraught wife was screaming at him and he had started drinking again. With his life and second marriage falling apart, the man said he needed help.

But the psychiatrist, Dr. Donald Levin, stopped him and said: “Hold it. I’m not your therapist. I could adjust your medications, but I don’t think that’s appropriate.”

Like many of the nation’s 48,000 psychiatrists, Dr. Levin, in large part because of changes in how much insurance will pay, no longer provides talk therapy, the form of psychiatry popularized by Sigmund Freud that dominated the profession for decades. Instead, he prescribes medication, usually after a brief consultation with each patient. So Dr. Levin sent the man away with a referral to a less costly therapist and a personal crisis unexplored and unresolved.

Medicine is rapidly changing in the United States from a cottage industry to one dominated by large hospital groups and corporations, but the new efficiencies can be accompanied by a telling loss of intimacy between doctors and patients. And no specialty has suffered this loss more profoundly than psychiatry.

Trained as a traditional psychiatrist at Michael Reese Hospital, a sprawling Chicago medical center that has since closed, Dr. Levin, 68, first established a private practice in 1972, when talk therapy was in its heyday.

Then, like many psychiatrists, he treated 50 to 60 patients in once- or twice-weekly talk-therapy sessions of 45 minutes each. Now, like many of his peers, he treats 1,200 people in mostly 15-minute visits for prescription adjustments that are sometimes months apart. Then, he knew his patients’ inner lives better than he knew his wife’s; now, he often cannot remember their names. Then, his goal was to help his patients become happy and fulfilled; now, it is just to keep them functional.

Dr. Levin has found the transition difficult. He now resists helping patients to manage their lives better. “I had to train myself not to get too interested in their problems,” he said, “and not to get sidetracked trying to be a semi-therapist.”

Brief consultations have become common in psychiatry, said Dr. Steven S. Sharfstein, a former president of the American Psychiatric Association and the president and chief executive of Sheppard Pratt Health System, Maryland’s largest behavioral health system.

“It’s a practice that’s very reminiscent of primary care,” Dr. Sharfstein said. “They check up on people; they pull out the prescription pad; they order tests.”

With thinning hair, a gray beard and rimless glasses, Dr. Levin looks every bit the psychiatrist pictured for decades in New Yorker cartoons. His office, just above Dog Daze Canine Hair Designs in this suburb of Philadelphia, has matching leather chairs, and African masks and a moose head on the wall. But there is no couch or daybed; Dr. Levin has neither the time nor the space for patients to lie down anymore.

On a recent day, a 50-year-old man visited Dr. Levin to get his prescriptions renewed, an encounter that took about 12 minutes.

Two years ago, the man developed rheumatoid arthritis and became severely depressed. His family doctor prescribed an antidepressant, to no effect. He went on medical leave from his job at an insurance company, withdrew to his basement and rarely ventured out.

“I became like a bear hibernating,” he said.

Missing the Intrigue

He looked for a psychiatrist who would provide talk therapy, write prescriptions if needed and accept his insurance. He found none. He settled on Dr. Levin, who persuaded him to get talk therapy from a psychologist and spent months adjusting a mix of medications that now includes different antidepressants and an antipsychotic. The man eventually returned to work and now goes out to movies and friends’ houses.

The man’s recovery has been gratifying for Dr. Levin, but the brevity of his appointments — like those of all of his patients — leaves him unfulfilled.

“I miss the mystery and intrigue of psychotherapy,” he said. “Now I feel like a good Volkswagen mechanic.”

“I’m good at it,” Dr. Levin went on, “but there’s not a lot to master in medications. It’s like ‘2001: A Space Odyssey,’ where you had Hal the supercomputer juxtaposed with the ape with the bone. I feel like I’m the ape with the bone now.”

The switch from talk therapy to medications has swept psychiatric practices and hospitals, leaving many older psychiatrists feeling unhappy and inadequate. A 2005 government survey found that just 11 percent of psychiatrists provided talk therapy to all patients, a share that had been falling for years and has most likely fallen more since. Psychiatric hospitals that once offered patients months of talk therapy now discharge them within days with only pills.

Recent studies suggest that talk therapy may be as good as or better than drugs in the treatment of depression, but fewer than half of depressed patients now get such therapy compared with the vast majority 20 years ago. Insurance company reimbursement rates and policies that discourage talk therapy are part of the reason. A psychiatrist can earn $150 for three 15-minute medication visits compared with $90 for a 45-minute talk therapy session.

Competition from psychologists and social workers — who unlike psychiatrists do not attend medical school, so they can often afford to charge less — is the reason that talk therapy is priced at a lower rate. There is no evidence that psychiatrists provide higher quality talk therapy than psychologists or social workers.