OPED NEWS November 26, 2010

by R.L. Cima, Ph.D.

My first contact with the psychiatric profession was in 1974. Armed with a new Bachelor’s degree in Sociology, I found work as a counselor at a 65 bed boy’s home in Corona, California.

I went back to college at 25 to get a bachelor’s degree so I could become a teacher and coach. I was a good coach. I commanded respect from the kids, I treated them with respect, I was in their face just like my best coaches were with me when I needed it, and I tried to help them improve on their talents and skills, no matter how old or what sport. I liked coaching almost more than playing. Coaching was my style at the boy’s home too, and it was effective.

Dr. Duncan was our MD. Dr. Duncan was a wonderful man. He donated his time, services, and money to the care of these teenage boys. Dr. Duncan was not a psychiatrist. Though there were psychiatric medications available to adults at the time, they were not in common use for children. However, Dr. Duncan sought out and found some new psychiatric training available to MD’s regarding some miracle chemicals available to help children. So, once he was trained, we began to medicate children.

Not all children mind you. It was the most difficult to manage children that were medicated, the ones the adults complained about the most. The explanation used by the experts at the time was that these children were hard to manage “because . . . ,” and then these same experts would say something vague about chemicals and parts in their brains that didn’t make sense. That’s when this whole idea of magical chemicals began to get fuzzy for me.

“because . . .”

“What is this Ritalin stuff?” I asked Dr. Duncan.

After all, I was giving these pills to kids, and I wanted to know what they were.

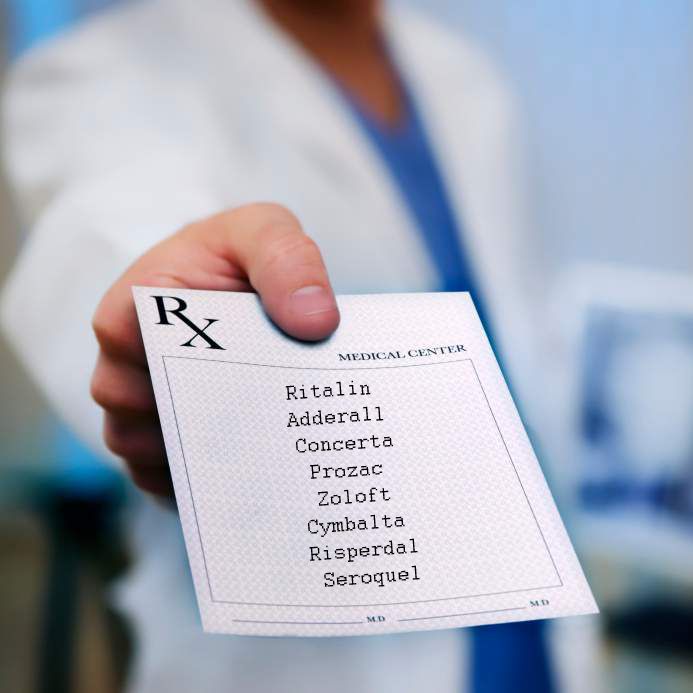

By the mid-seventies, Ritalin was quickly becoming the treatment of choice for hyperactivity, or what was then called “hyperkinesis.” A few years later Attention Deficit Disorder was coined, and by 1987, ADHD was voted in as a new disease in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM).

I used to keep the pill packets in my shirt pocket. I gave them to the kids as prescribed, usually after dinner or before bed. All I noticed is that the kids had a tough time going to sleep, and often were groggy in the morning. That was explained to me as a “side effect.” I came to quickly hate that term. There was nothing “side” about it. These were full-blown effects.

“It’s a stimulant,” Dr. Duncan answered.

I thought that was odd. A few of the boys I was giving it to were arrested and placed on probation because they were taking stimulants, usually Benzedrine (“bennies”).

“Why do we give it to kids already too stimulated?” I asked.

This is where it begins to get tricky.

“We don’t know,” Dr. Duncan would say. “It’s what they call a “paradoxical effect.'”

This made me nervous. You see, I’m a bit of a skeptic. Skeptics make good scientists and terrible blind proponents. My ears perk up when I wait to here someone answer a why question, about anything.

To begin with, I wanted to know who “we” and “they” are, and I wanted to know how “we” and “they” know what they say they know. Besides, saying something like “paradoxical effect” doesn’t explain anything. It’s just another way of saying “we” and “they” don’t have a clue. I continued:

“But that doesn’t make any sense,” I deplored of Dr. Duncan. “How can a stimulant calm a kid down?”

Seems like a reasonable question, doesn’t it? Why would something that’s given to narcoleptics to “perk them up” be given to kids who need to “perk the hell down.” How does a chemical act as a stimulant for adults, and as a sedative for children? How does a chemical know how old someone is?

The reply to this? Well, it was the same from all MD’s and other experts that I knew at the time, because I would persistently and annoyingly ask. At some point the conversation usually ended with, more or less:

“. . . shut up and give him the pills.”

I had a degree in sociology for chrissake. So, I gave them the pills.

But I didn’t shut up.

A Very Private Practice

One day, a boy had to be hurried to the psychiatrist. The doctor’s office called and said there was a last minute cancellation, and my supervisor picked me to take him to the doctor’s office.

I was a little nervous. I had pestered this doctor with my questions, apparently to the breaking point. I was nearly 30 by then, I had two kids of my own, and I wanted clear answers. I don’t do well with platitudes. I guess it showed. At some point he decided he didn’t want to answer any more of my questions, especially when he found out I had a bachelor’s degree in sociology. So, this time, I walked in with one of the boys and I quietly found a seat. The boy was soon escorted to a room in the back where he would wait to see the doctor.

It was late in the day and the office was empty. I took a seat just below and to the right of the sliding glass window where the receptionist was. I was extra quiet. After a few minutes, I was out of sight and, as I soon found out, out of mind.

About 10 minutes later, I heard the doctor approach the receptionist area. The receptionist, I would learn, also did the doctor’s billing for Medi-Cal. Her name was Evelyn. I remember her name because, unbeknownst to the doctor, this is what I heard the doctor say to her, in no uncertain terms:

“God dammit Evelyn, how many times do I have to tell you?! I don’t get paid for this diagnosis!!”

Hmmm. As I was to learn in the next few years, the love of money really is the root of all evil after all.

Jimmy

A few years later my wife and I were running an 8-bed facility for teenage boys. We were independent. We were the child’s counselor, social worker, and therapist all in one. There weren’t any licensed, master’s level therapists yet in California, and if you had a bachelor’s degree you could do most anything.

With one of our best friends at the time working on the weekends, the three of us were very successful. We had a work ethic, and the kids were busy around the house. We made sure they got a lot of recreation, we fed them well, we included their parents in the program from the beginning, and at the end of two years all eight were attending public school. One 12 year old boy, Rodney, was playing little league, and another 16 year old, Jimmy, was taking piano lessons. Jimmy was the reason I stopped medicating children.

He arrived drugged. He was a perfect medication icon. He had been in and out of a number of facilities from the time he was five, never completing a program and, according to his parents, had just gotten “worse and worse.” He was verbally aggressive, sometimes physically aggressive, but mostly he was defiant. Tell him to go left, and he went right. You get the picture.

One day, about three months into our home, during a common confrontation, I told him to do something or not do something, I don’t know which. It doesn’t make any difference. It’s what adults do with teenagers. He explained his non-compliance to me rather matter-of-factly:

“I can’t help it. I’m hyperactive.”

This bothered me. Though I’d heard it before, this time it was done with what I though was way too much self-assurance on Jimmy’s part. I think he kind of smiled when he said it. I was caught in the same dilemma as everyone is who adheres to the Disease Model. If it’s really a disease and out of a person’s control, why does anyone expect them to control it when you ask them to?

In any event, I replied to his nearly proud declaration, just as matter-of-factly:

“Not anymore.”

With his parents’ blessings, we stopped giving him his daily chemical the next day. That was the last time I ever gave a child a psychotropic chemical that was under my direct care.

Jimmy improved. With time, trust, persistence, old-fashioned parenting, educated guidance, and Jimmy’s gutsy fight to become normal again, he improved. So did his confidence. He was “cured” of a disease he never had. Despite the cautious and pessimistic hand wringing by all the medics that had known him, he was relieved and so were his parents. Now, when he acted like a jerk, he was just a jerk. He wasn’t sick, nor was he “out of control.” In time he went home to his family.

I think it went to my head, just a little.

First Date: Meeting a Live Psychiatrist

About a year later we received a call from the Department Head at the psychiatric hospital located in the UCLA Medical Center. Pretty big stuff. The doctor said he had a boy there, Mark, who has been with them for about four months, and would I be interested in meeting with him to see if he would be an appropriate placement in our home. Sure, I said. Bring him out.

Mark was 15 and overweight. He had gained 40 pounds while at UCLA. This was common in psychiatric settings. There were still some “psyche hospitals” for kids back in the ’70’s in California and I was familiar with several. They all looked the same. Locked doors everywhere, little if any outside recreation areas or equipment – nor the inclination to provide any – locked rooms where “crafts” and groups occurred, always populated by unhappy children and unhappy professionals, with all those new medications leading the way. They weren’t treated as kids in these places. God help them, they were treated as patients with diseases. They still are.

Mark and his doctor showed up for an interview the next day. He told us about Mark’s history again, and he let us know Mark was “clinically depressed.” Sounded serious. He told us about what his hospital did, he told us about the professionals there and the papers they’ve written and will write, and in general, overwhelmed us with credentials, experience, and vocabulary. He then told us this:

“Before I forget, Mark is taking 1500 milligrams of Lithium a day because of his depression. I’ll make sure you get his medication and a new prescription until you can get him to your psychiatrist.”

Does 1500 mg seem like a lot to you? It did to me. OK, maybe I wasn’t sure what a milligram was, however, 1500 seemed like a big number. Also, from my point of view, given his history, it would have been strange had he not been depressed. And what the hell is lithium?

Lithium is a salt. It was used to treat gout in the 19th century because scientists discovered that lithium could dissolve uric acid crystals from the kidneys. However, to do this successfully, you had to use so much lithium that it was toxic – poisonous – to human beings.

Not to worry. There were theories at the time that uric acid was “linked” to a range of disorders, including depression and mania. Danish physician and psychologist Carl Lange and the American neurologist William Alexander first started to use lithium for mania in the 1870″s, though it’s use was, for a number of reasons, abandoned by the turn of the 20th century.

In 1949 it was “rediscovered” by John Cade , an Australian psychiatrist. He also prescribed it for mania patients. Though slow to catch on by the treatment profession because of its toxic nature, after much lobbying, lithium was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 1970.

Now back to that head psychiatrist from UCLA, Mark, and me.

After hearing his best medical advice, I said to the psychiatrist in a firm yet respectful manner:

“I’m going to take him off his medication when he gets here.”

His response was equally respectful, as though I hadn’t heard everything he said. So, he repeated himself, explaining again how serious Mark’s disease was, and that he had to be on this medication – probably for life – or there would be serious and dire consequences to his health and well being. To this I said:

“I’m going to take him off this medication when he gets here.”

This time he was angry and accusatory. He made it clear he did not approve and that it was evident I didn’t understand. I fully expected him to get up, grab Mark, and leave, huffing and puffing his way out the door. He didn’t.

He placed Mark with us instead.

So much for his conviction, I said to myself, this medical doctor who was the head of the psychiatric department at UCLA. He placed him with me because Mark was a management problem and he wanted to get him out of his hospital. If he was true to his science, he would have driven him back to Westwood, cursing me as he did. He either didn’t believe what he was saying, or it didn’t matter to him.

Either way, we were glad to have Mark in our home.

We took him off his chemicals immediately, with mother’s approval. Within four months, he had taken off all his weight and he fit in with the rest of the kids. There were, of course, the same problems along the way that we had with Jimmy. That’s the nature of our business. We eventually sent him back home to his mother a year later.

For the next few years I was promoted to ever increasing responsibilities. I had little regard for the psychiatric profession and this practice by then. There were times when I would be training others, and I would steer the conversation to this subject, just so I could say:

“If we gave this many chemicals to animals, the ASPCA would be screaming.”

Chemicalizing children was a growing “truth” among professionals, and I was out of sync. Nonetheless, I thought the practice was despicable. Most important, I never saw any improvement, in any of the kids, at any time.

To me, this was child abuse.

Keirsey

A bout this time, colleagues convinced me I should go back to school to get my Master’s degree if I wanted to be taken serious, so I did. By 1979, I started at Cal State University in Fullerton. I was going to get my Master’s Degree in Counseling Psychology and, along with learning new skills, I hoped I was going get to the bottom of the medication thing.

I knew I was enrolling as a little fish from a little pond. It’s one thing to be a little cocky based on self-proclaimed successes. It was quite another to go into a field where chemicals were being touted as the second coming. I didn’t think I’d fit in, and I knew I wouldn’t be able to keep my big mouth shut.

I was a little trepidatious, to say the least.

My first class in my first semester was counseling 735. It was also the last class for Dr. David Keirsey before he retired from a long career. He had already written Please Understand Me with Marilyn Bates. Since then he has written several other books, including his seminal work, Please Understand Me II. He is the preeminent temperament theoretician in the world. If you want to understand human behavior, and yourself, read this book. Millions of others have, around the planet.

As the Department Head for the Counseling/Psychology Department and he developed a unique program based on the practice of doing therapy rather than learning the various theories of therapy. He was also a walking bibliography when it came to the history and evolution of human psychology. That made it easy for me. Why go through all the pain of reading this stuff if he already had, I reasoned to myself. Better to see if he had anything worth saying.

Turns out he did. A number of things. A few that changed my entire view of psychology, including an orientation to Holistic Theory that I will reserve for another time. It was at one of his initial lectures that my ear perked for the first time. There were only fifteen of us in the class, so it was comfortable.

He somehow got onto the subject of medicating children. Before academia, he had a career as a child psychologist. He worked with troubled kids in a variety of settings. He had an opinion. He expressed it, and when someone pressed him as to what, exactly, did he mean, he turned, looked at his student, and declared:

“I said I think it (the practice of medicating children), should be criminalized.”

Did I hear just him right? Did he just say that giving these chemicals to children should be against the law? Yes he did. I sat up in my chair. He didn’t sound at all like that doctor from UCLA. If I were hearing him right, he would have had that doctor locked up.

This was affirming. Though he was unknown to me, this was Dr. David Keirsey, Clinical Psychologist, and the head of the Counseling Psychology Department at Cal State Fullerton.

But it wasn’t just that. I’m not so easily impressed by credentials or experience. Fools often have all the right credentials and experiences. I had met a lot of them already. No, it was that there were voices out there in the professional world that had long ago came to the same conclusion as I. This was just the first time I heard it. This meant my views had professional merit.

By 1983 I was immersed in my Master’s program. I took work as an Admissions Director at a 120-bed agency. I was a vocal critic of medication for any kids at any time. I did many training seminars about strategies and techniques in child management, and I always folded this subject in, indicating that the practice was (1) unproven, (2) ineffective, (3) detrimental to children, and I would list the evidence for each. I was not persuasive, and I still had that damn degree in sociology.

It didn’t matter. No one paid attention. The chemical wave had started.

The APA

Around this time, I was sitting in a barbershop on a Saturday morning, waiting my turn. I was thumbing through a psychology magazine. I ran across an article written by someone from the American Psychiatric Association. The APA is a member based lobby group.

Back then psychiatrists were still doing therapy while their client was on a couch, staring at the ceiling, and disclosing his or her most private thoughts and feelings. Troubled adults went to their psychiatrist to talk with them about their troubles, and the relationship they had with their doctor was very important.

More and more often, according to the author of the article, psychiatrists were giving their clients different doses of different chemicals to ease some of their symptoms. This was understood to be an addendum to the real therapy that took place in a quiet office for an hour. After all, a psychiatrist is first an MD, and if there are medicines available to ease symptoms, they could be used with certain clients. Once medicated, then the therapy in the office could continue with better results.

This article was concerned with a developing trend: there were a growing number of psychiatrists who were relying too much on medication. The author, also a psychiatrist, went on to warn that it seemed like many psychiatrists were abandoning more traditional forms of therapy, and were succumbing to the appeal of giving their clients chemicals to curtail symptoms, and in so doing minimizing, and sometimes eliminating, traditional “talk therapy” sessions.

Psychiatry, the author feared, was turning away from psychology and towards medicine when it came to helping their clients with their persistent life problems. The tone of the article was cautious and meant to discourage their members from getting too far from the couch. It didn’t take.

Now, quickly, roll the clock forward 15 years. By 1999, I was the Executive Director for a new wraparound program. We had a contract with a County Mental Health Department in California. While we were an independent, private, nonprofit agency, the contract was clear that we would defer all medical decisions to the county psychiatrist. Any adult or child in the Mental Health system was required to be reviewed by a psychiatrist. Funding depended on it.

We attended a weekly meeting along with other providers and county personnel. The psychiatrist sat at the head of the table while therapists would review client progress. Based on this information presented, the psychiatrist would prescribe an increase or decrease of a chemical, leave it the same, or change the chemical to something more effective.

On this day, one of the therapists from another program was exasperated. Her client was not improving, and in fact was getting worse. With the best of intentions, and desperation, she was seeking support and assistance, so she asked the psychiatrist:

“Would you mind talking to my client yourself, just to see what you think?”

I perked up, again, like I always do when something interests me. I wanted to hear his answer. I thought it put him on the spot and I didn’t mind him squirming a bit. Once again, I underestimated the implied ascendency that accompanies psychiatrists.

In an angry, frustrated, and accusatory tone, he replied to this young, uninformed therapist, and everyone else in the room in case they needed it, slamming the palm of his hand on the table for emphasis as he did so (beginning the same expletive as the first psychiatrist!):

“God dammit!! When is everyone going to finally understand?! Psychiatrists prescribe meds!! That’s it!!”

And that was it. He made it official. There was neither need nor inclination to pretend psychiatrists did anything else. In just 15 years from the time I read that cautious APA article, the author’s concern had been addressed and firmly answered.

Psychiatrists had kicked their couches to the curb, got a lifelong supply of prescription pads, and became engaged in their work: prescribing chemicals for every human shortcoming known from the past through the present, fully prepared for the future’s crop of diseases. “Talk therapy” was demoted to others without prescriptive powers. Without anyone noticing, talking directly to the client for an hour about his or her problem was no longer necessary, and by some frowned upon, in the scope of practice for the psychiatric profession.

The relationship between patient and psychiatrist was no longer important.

I knew by then there was a small but growing number of professionals who saw this for what it is: a vast marketplace worth billions a year, and a remarkable era on earth when well-meaning adults give harmful chemicals to children for diseases they don’t have.

Finally, I completed my Master’s degree in 1984, and I was awarded a doctorate degree in Psychology in 1987.

I know the science.

So will you.

http://www.opednews.com/articles/2/Your-Kids-Aren-t-Sick-by-R-L-Cima-101123-643.html